In Timor-Leste, a small island near Indonesia, many supporters are working to amplify the voices of the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” victims, who have been marginalized amid government indifference and social stigma. Meanwhile, a professor in the United States across the Pacific is teaching university courses on the history of “Comfort Women,” a subject rarely mentioned in textbooks, and emphasizes that society can stop violence against women by facing the dark sides of the past. Furthermore, some argue that making the history of “Comfort Women” an international official record is crucial to prevent the repetition of such an unfortunate history.

Bringing the invisible victims back to the center of attention and recognizing the “Comfort Women” issue as a universal human rights issue for everyone living in the present, rather than a past issue of a few, is the starting point of the “Comfort Women” discourse. In commemoration of the 2024 International Memorial Day for Japanese Military “Comfort Women,” the webzine Kyeol introduces various movements made at home and abroad to bring the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue, which has lingered on the periphery of history, to the forefront as a core agenda of women’s rights.

Interview with Associate Professor Jing Williams of Social Studies Education & Phyllis Kim, Executive Director of “‘Comfort Women’ Action for Redress and Education (CARE)” (2)

Kyeol : In Korea right now, historical revisionism that denies and distorts the forced mobilization of “Comfort Women” is gaining strength. As these claims spread widely on the internet, students who encounter them often attack their teachers or disrupt classes. Do you see a similar atmosphere in American society?

🧶 Jing Williams : In fact, I have never experienced denial or attacks while teaching about the “Comfort Women” issue in the U.S. When preparing materials, I base them on historical sources such as those provided by “Comfort Women” Action for Redress and Education (CARE), Japanese government records regarding the transportation of the “Comfort Women,” and testimonies from U.S. soldiers. In addition, My lectures foster discussion and debate, making it challenging to adopt an aggressive stance. However, since there are still those who deny this history, I explain we must combat these false opinions.

The Importance of Lesson Plans and Teaching Materials in Educational Settings

🧶 Phyllis Kim : In 2016, during our campaign to include the Japanese Military “Comfort Women” issue in the California state curriculum, there was a large public hearing hosted by the California Department of Education. At that event, where various issues were discussed, claims were made that the “Comfort Women” narrative was a lie, that they were prostitutes, and that the issue should not be included. However, the board of directors ultimately decided to accept our argument. In the final moments, a representative from the Department of Education announced, “There have been several hotly debated issues, one of which is the ‘Comfort Women’ issue. Due to conflicting opinions, we decided on a compromise: to include the ‘Comfort Women’ issue along with a statement that the governments of Korea and Japan reached an agreement on the issue in 2015, and to include a link to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs.” The amendment passed in that form. Later, we found out that not only the Japanese government but also the Korean government had requested the Department of Education to include it in that way. We were dumbfounded.

That’s why having well-prepared lesson plans and materials for use in educational settings is so important. Since the “Comfort Women” issue was included as a topic, we created resources to help teachers, making these materials available online for easy access. Once, at a social studies conference, a professor visited our booth and mentioned that they were developing materials on the “Comfort Women” issue for California teachers. We were pleased and offered to provide feedback if they shared the draft with us. When the draft arrived, we found it had a strong Japanese perspective and extensively analyzed the 2015 Korea-Japan “Comfort Women” Agreement, relying heavily on inappropriate sources. Given Japan’s significant budget for spreading distorted claims, it must have been easy to access such information. I immediately contacted them, provided numerous references and materials, and asked them to correct any inaccuracies or potential misunderstandings, assuring them that it was fine not to mention us as the source. Fortunately, although not all our suggestions were incorporated, many were reflected in the final product.

On the one hand, it was quite disappointing to see Korea’s passive approach to providing various resources, in contrast to Japan. It has been over 30 years since the “Comfort Women” survivors gave their testimonies, yet there is a significant lack of academic “citations” and official evidence that can be referenced. For teachers, students, and researchers alike, what source could be more important and truthful than the testimonies of survivors? While Japanese official documents are crucial primary sources, the survivors’ testimonies contain much more truth that isn’t captured in those documents. Accompanying the “Comfort Women” survivors on speaking tours, I can’t help but realize how powerful the voices of the survivors, or victims, are as resources. In the U.S., there is a focus on a “victim-centered approach,” emphasizing the importance of hearing the voices of suppressed victims. This makes it extremely important for the voices and vivid testimonies of the “Comfort Women” survivors to be properly conveyed. Unfortunately, there is very little academic collection of testimonies that can be cited. I want to stress that this is an issue that needs to be resolved urgently.

Kyeol : It seems that our Research Institute on Japanese Military Sexual Slavery (RIMSS) has been assigned an important task.

🧶 Phyllis Kim : While the translated collection of testimonies has been published as non-commercial items, many survivors have been anonymized. It is essential to provide an English version that includes explanations of the historical context, cultural differences, and clarifications to address potential misunderstandings of the victims’ testimonies that may arise for various reasons. We are also concerned about the Japanese government’s well-funded historical revisionism and make significant efforts to ensure we are not swayed by it.

Kyeol : When using lesson plans or teaching materials, you may encounter ideas for modifications or areas that need improvement in the classroom. Do you have any episodes to share from your teaching about “Comfort Women”?

🧶 Jing Williams : Since I spend a lot of time preparing the materials, most students are satisfied. They deeply empathize with the experiences of the “Comfort Women” victims and form an emotional connection. In a post-lecture survey, I asked what they would like to say if they could meet one of the survivors. One response stood out: “I honestly don’t know what to say. No words could offer sufficient comfort. However, I want you to know that we have heard your story, we know it, and we have not forgotten it. We feel angry on your behalf, so you shouldn’t be mortified.”

“The Biggest Challenge: Protecting My ‘Comfort Women’ Lecture”

Kyeol : There must be challenges in the process, such as the difficulties you face as an educator teaching the “Comfort Women” issue in American society.

🧶 Jing Williams : I believe my lectures must always be effective and practical, but they also need to be somewhat relevant to the state of South Dakota. What I mean is that the topics I teach should align with the state’s educational standards. South Dakota is a very conservative state, and the governor doesn’t particularly support “Global Studies.” High schools in South Dakota teach why World War II broke out and how it affected the entire world. I approach the topic of “Comfort Women” as a part of that war and history, but for me, the biggest challenge is protecting my lecture itself.

🧶 Phyllis Kim : Speaking of my challenges, every activity I undertake is a challenge. Education doesn’t occur solely in the classroom. Our organization’s name is “‘Comfort Women’ Action for Redress and Education (CARE),” which has two main components: redress and education. Redress encompasses not only monetary claims but also all efforts to restore the original state, which is the literal meaning of “redress” in English. In that sense, every campaign aimed at delivering justice to the “Comfort Women” victims, our medical support initiatives, and the installation of the Statue of Peace are all part of our redress activities.

Educational activities often overlap with campaigns and activism for redress. For instance, our efforts to install the Statue of Peace and the “Comfort Women” Memorial serve both as redress and educational activities, creating educational effects in the process of raising awareness. The same applies to our collaborations with individuals promoting the installation of the Statue of Peace, conducting campaigns, holding conferences, and creating educational materials for distribution in local languages, such as German.

We also continually create new initiatives. To engage students, we hold a contest every year. In the first year, it was a drawing contest, followed by a video contest in the second year, and an essay contest in the third year. Students have become increasingly enthusiastic, producing creative and excellent works. For example, a high school student reached out to us wanting to create an animated documentary, so we connected the student with Lee Yong-soo, resulting in an impressive 10-minute animation. Since last year, we have provided scholarships to six universities in the United States. Scholarship recipients undertake projects that can take the form of artwork, films, music, or research. We gather all the works and hold a presentation event. This year’s program is ongoing, and in July and mid-August, four of the scholarship recipients will visit Korea. It would be great if they could also visit the RIMSS. Some professors have expressed interest as well. This way, we are planting small seeds to ensure that interest in the “Comfort Women” issue becomes a natural part of American society.

We worked on the "Eternal Testimony Project," and we're currently developing an online archive under the "UCLA Center for Korean Studies," based on the first translation project conducted with RIMSS's support. The archive includes not only the annotated primary sources but also testimonies and interviews of the survivors featured in documentaries and animations. Additionally, we plan to upload teaching materials, such as lesson plans, in the near future.

Another important aspect of memorial building is to continue local activities at the location of the memorial. We held memorial services in Glendale every time a “Comfort Women” victim passed away. Community compatriots consistently attend, including individuals from the Chinese and Armenian communities, to pay their respects together. To maintain ongoing interest, we also host annual events. Last year, we organized a major event for the 10th anniversary. This year, we are holding an exhibition at the Museum of Social Justice, run by the city of Los Angeles, focusing on the “Comfort Women” issue. The exhibition highlights the voices of the survivors and includes student artworks. Professor Williams has also been a great help in this effort.

Professors interested in the “Comfort Women” issue often invite me directly to share insights. They aim to educate students about the activist perspective. The reason this issue has gained recognition and support is that various campaigns have sparked discussions and controversies, leading to a greater interest in understanding the underlying causes. They teach students that grassroots movements are essential for social change. These professors ask for updates on our activities. When we share what we’ve done in the U.S. regarding the “Comfort Women” issue, students show great interest. Later on, some students maintain this interest and seek ways to contribute, often due to connections formed in high school. It’s incredibly rewarding to witness this engagement.

Preparing the First Publication on How to Teach the “Comfort Women” Issue in the U.S.

Kyeol : You briefly mentioned the Glendale Statue of Peace. Given the sensitive issues surrounding it, we would like to ask about the current status of the Glendale Statue of Peace.

🧶 Phyllis Kim : The highly symbolic Glendale Statue of Peace was erected on a site that was officially approved by the city council and provided by the city. Although there have been some minor changes to the site, it remains well-protected because it is city-owned. The statue also withstood a Japanese lawsuit aimed at its removal. We insist on placing the statue in public spaces for this very reason—to ensure its safety and stability. While we occasionally hear that the removal of the statue remains a top priority for the Japanese Consulate-General whenever there’s a leadership change, there is no significant concern regarding the Glendale Statue of Peace.

Kyeol : That’s great to hear! Both of you have collaborated and accomplished a lot, much like activists. During our research, we discovered that you are currently working on publishing a book together. We're curious about the progress you’ve made and what content each of you plans to include.

🧶 Jing Williams : Last year, Executive Director Phyllis Kim and I attended the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) Conference, the only social studies teacher organization in the U.S at the national level. We discussed the need for a reputable and well-known publisher to publish books related to the “Comfort Women” issue, thinking teachers could learn a lot from it. Despite our efforts, we couldn’t find a suitable publisher. We then proposed the idea to NCSS, believing that if NCSS published it, many teachers would trust its credibility and use it. NCSS showed a lot of interest in our proposal, and if published, this would be the first book on how to teach the “Comfort Women” issue in the U.S. However, NCSS advised us to include related topics such as human rights and gender issues.

To give you a brief overview of the table of contents, the first chapter begins with the question: Who are the “Comfort Women”? The structure includes several chapters, each containing related content and a 45-minute lesson plan. Some of the questions addressed include: Who are the “Comfort Women”? How did the world become aware of the issue? How does the Japanese government respond to this issue? What is the Wednesday demonstration? How is the U.S. responding to the issue? Why are the testimonies of the “Comfort Women” such a heated debate? What stories are the surviving “Comfort Women” sharing? What are the contents and issues surrounding the 2015 Korea-Japan “Comfort Women” Agreement? Do “Comfort Women” have human rights? What is the most recent incident of denial regarding the “Comfort Women”?

As I mentioned, each topic will include relevant content alongside a lesson plan, making this publication a resource for both learning history and understanding how to teach it. We will also compile testimonies and materials from the “Comfort Women,” as well as a list of English children’s books and documentaries containing content about the “Comfort Women.” Our goal is to provide a rich array of resources to help future teachers create lesson plans.

🧶 Phyllis Kim : We aim to create a book that will give teachers the confidence to teach this topic with assurance. Although it feels a bit burdensome to say this in advance, we are working hard to have it published next year.

Kyeol : We hope the publication will also be utilized in domestic education. Once the book is released, we believe it will inspire teachers in Korea as well. Are there any opportunities or methods for history teachers in the U.S. and Korea to collaborate?

🧶 Phyllis Kim : In fact, there have been several collaborations among teachers from Korea, China, and Japan, and I know that the Asia Peace and History Institute is also engaged in meaningful activities. However, What I find challenging due to the nature of Korea is that the “Comfort Women” issue is often viewed from an overly nationalistic perspective. In the U.S. and other countries, it is seen as a universal women’s human rights issue. There is an expectation and hope that adopting this broader perspective could bring about significant changes in the perception of the “Comfort Women” issue within Korean society. I believe that the role of teachers can be a crucial factor in this regard. I want to extend my support to all the teachers.

Topic

#Education #International Community #Social Movement #Asia-Pacific

Region

USA

Compiled by the Editorial Team of Webzine

Terms

#Eternal Testimony Project #Los Angeles Riots #The Apology #US Congressional Resolution Demanding Japan’s Apology for the Japanese Military “Comfort Women”

Related contents

-

- “Teaching the ‘Comfort Women’ Issue in the U.S. Society: A Global Citizenship Education to Overcome Nation-Centrism”

-

Professor Jing Williams considers her education on the “Comfort Women” issue as “a process of planting seeds for the future,” recognizing that some of her students may become advocates for women’s human rights.

-

- 김복동을 기억하는 사람들 〈상〉 - 단상 위의 김복동

-

[기림의 날 특집] 인권운동가, 평화활동가로서 김복동의 활약을 곁에서 지켜본 사람들이 기억하는 그는 어떤 모습일까? 류광옥 법무법인 가로수 변호사, 윤지현 전쟁과여성인권박물관 자료팀장, 백시진 정의기억연대 및 팔레스타인평화연대 활동가, 김현정 배상과교육을위한위안부행동 대표의 기억을 담았다.

-

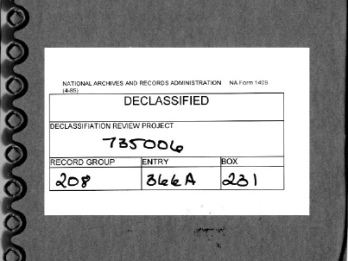

- U.S. Office of War Information Report No. 49: A report reflecting the author’s subjective bias

-

Japanese far-right forces have been attacking Japanese Military “Comfort Women” victims based on the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) Report No. 49.

- Writer Jing Williams

-

Originally from China, she completed her Master’s in English Language and Literature, Translation at Tianjin Normal University and earned her Ph.D. from Ohio University in 2014. She currently serves as an Associate Professor of Social Studies Education at the University of South Dakota, USA, where she teaches elementary and secondary social studies methods courses. She has published numerous papers focusing on global perspectives in social studies education in journals such as the Journal of Sociological Research, International Journal of Sociological Research, and International Journal of Education.

- Writer Phyllis Kim

-

Since participating in the 2007 campaign for the “US Congressional Resolution Demanding Japan’s Apology for the Japanese Military ‘Comfort Women’,” she has founded and led the “‘Comfort Women’ Action for Redress and Education (CARE),” which aims to raise awareness about the issue in the United States. She is also actively involved in domestic initiatives, including the “Eternal Testimony Project,” and is currently developing an online archive at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).