Pondering the 'comfort women' issue in a new light

The supranational nature of the 'comfort women' issue and the ‘glocalization’ of memories

What is the ultimate meaning of the "resolution of the 'comfort women' issue" that so many people have been calling for so far? The domestic and international affairs over the past three years after the Korea-Japan Agreement of December 2015 which declared the resolution of the 'comfort women' issue makes one question again the appropriateness of the framework of a bilateral agreement between the South Korean and Japanese governments in resolving the 'comfort women' issue.

The Supreme Court of Korea's 2011 decision of unconstitutionality2 prompted the South Korean government to launch full-scale negotiations with the Japanese government to resolve the 'comfort women' issue. This subsequently raised the anticipation that South Korea would put forward a prudent model guiding how victimized countries should tackle grave human rights issues such as sexual violence perpetrated by states. However, South Korea and Japan reached an agreement via dubious and secretive negotiations mainly to end the dispute in haste, and thereby disappointed the victims and civil societies. To what extent did the negotiation to resolve the 'comfort women' issue, which is one of the pathways to achieving better South Korea-Japan relations, consider women's rights, sexual violence, and the role of the victimized state?

Grandmother Kim Bok-dong, who had been most actively opposed to the Korea-Japan Agreement and had been also a survivor and peace activist herself, passed away recently. Only few survivors are alive as of spring 2019, and the "comfort women issue" is still ongoing. Thanks to the backlash against the agreement, the 'comfort women' issue is rather facing a new turning point now. Wednesday Demonstrations are adding new participants at each rally, and the younger generations are displaying more sympathy towards the 'comfort women' issue than the older generations. Now, it seems that we are urged to ponder the issue in different ways, to go beyond the framework of the "resolution" through the perpetrator’s remorse, such as sincere apologies from the Japanese government or the admission of legal responsibilities.

So far, I have been arguing that the 'comfort women' issue should be understood from the world history perspective such as the development of international human rights law for women, to transcend the cognitive framework that merely focuses on national interests, such as national history or the South Korea-Japan relations. The scope of the 'comfort women' victims reach far beyond South Korea, to include women in various Asian countries that Japan fought as well as Dutch women residing in Indonesia. In other words, the characteristic of the 'comfort women' issue itself is international in nature. Also, interests in the 'comfort women' issue also parallel the development of international human rights law for women that criminalize wartime sexual violence, which was used as a weapon of war in frequent ethnic conflicts during the early 1990s. In that process, the 'comfort women' issue became recognized as an example representing the violation of women's human rights by the state in the 20th century, and efforts to prevent its recurrence through the education of future generations and collective memory became one of the common challenges for humanity.

Thus, the 'comfort women' issue has been perceived as a supranational problem surpassing South Korea-Japan relations. This article reviews the supranational and global nature of the 'comfort women' issue from six perspectives as discussed below.

1. The 'comfort women' issue is the war damage shared by Asian countries

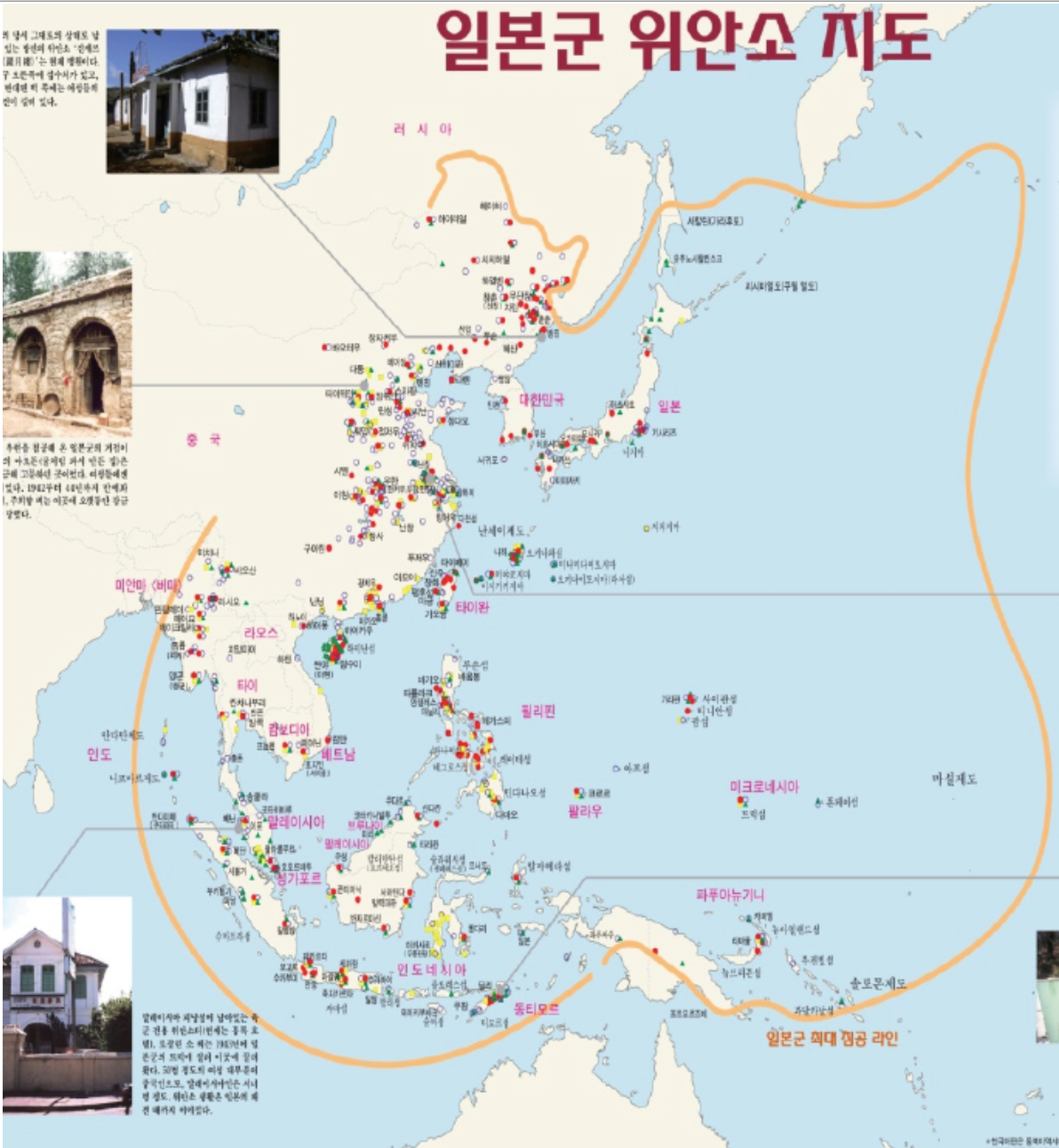

First, let us look at the status of the damage related to the 'comfort women' issue. The 'comfort women' issue is not limited to Korea (Joseon) alone, but is widespread as the shared war damage across the Asia-Pacific region, where Japan fought the Pacific War.

As shown in the map marking the distribution of comfort stations, studies so far have identified hundreds of comfort stations dispersed throughout each region in Asia and the Pacific. The 'comfort women' in Japan, Joseon, and Taiwan were forcibly recruited and were managed mainly under military involvement. In other areas, local women were recruited or kidnapped for the establishment of comfort stations, or were locked up via kidnapping or violence and were then raped. The estimated tens to hundreds of thousands of Asian women subsequently became the victims of various forms of sexual violence in comfort stations for ‘comfort women’ or in battlefields. Most of the survivors lived on by hiding their damage even after the war, but Kim Hak-sun's testimony in 1991 prompted some of them to emerge in the world as the "'comfort women' victims". Nonetheless, the 'comfort women' issue remains unsolved and thus a common challenge for Asia.

2. The 'comfort women' issue holds meaning in terms of the history of global human rights law for women

Since becoming visible through Kim Hak-sun's testimony in 1991, the ‘comfort women’ issue soon emerged as a global issue, and thereby contributed significantly to the formation of the international human rights law for women which progressed rapidly in the 1990s. When South Korean women initially raised the issue officially to the Japanese government in 1990, the Japanese government denied state responsibility on the grounds of a lack of evidence. In response, support groups decided to raise the issue to the United Nations Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (UN SCPPHR) in order to elicit a sincere attitude from the Japanese government. In 1992, the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan raised this issue to UN SCPPHR. The ‘comfort women’ issue was also raised by Japanese civic groups to UN SCPPHR in February of the same year, and was again raised in May of the same year at the Working Group on Contemporary Forms of Slavery along with the issues of people abducted for forced labor.

The issue received a great deal of attention, resulting in a visit of UN SCPPHR's Special Rapporteur Theodore Van Boven to South Korea to address the issue of 'compensation and rehabilitation for victims of the gross violations of human rights'. In December, experts from international human rights organizations held a public hearing in Tokyo to hear the testimony of South Korean victims. According to a Japanese lawyer who raised the 'comfort women' issue with South Korea to the UN at the time, the 'comfort women' issue generated more immediate attention than any other human rights issues related to Japan had raised in the past.

Global women's human rights networks which had been tackling the issue of violence against women also showed a highly enthusiastic response. In particular, the World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna3 in 1993 was a major turning point in the development of human rights law for women, as the 'comfort women' survivors focused on elucidating the truth about the 'comfort women' issue by testifying directly at the World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna in 1993. As the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna was held to reflect on the failure of the existing human rights regimes in properly responding to human rights issues that had emerged as a major concern after the Cold War, women's organizations from around the world participating in this conference criticized that the existing human rights regimes were male-centered. They strongly raised the issue of violence against women with the slogan "Women’s Rights are Human Rights". Amid these movements, the UN General Assembly adopted the 「Declaration of the Elimination of Violence against Women」 in December of that year.

In response to the demands of women's organizations, the final resolution of the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna included a call for the creation of a Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women for the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR). Appointed as the first Special Rapporteur in 1994, Radhika Coomaraswamy submitted an investigative report on violence against women examining the 'comfort women' issue to UNCHR. It was the first report by a UN agency that addressed the 'comfort women' issue, and in this process, the 'comfort women' issue attracted international attention to transform into a global human rights issue. In the 1995 United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women held in Beijing, the elimination of violence against women was discussed as a main task, and the 'comfort women' issue continued to be addressed as an important subject.

In the early 1990s, the world was paying attention to crimes against humanity such as those involving mass rape and rape centers particularly during ethnic conflicts such as the Bosnian War and the Rwandan Civil War. Those two wars led to the trials of war crimes at the International Criminal Court in 1993 and 1994 respectively, during which sexual violence and the mass rape of women were recognized as deliberate means of warfare, and these forms of deliberate sexual violence were subsequently acknowledged as 'crimes against humanity'. Afterwards, the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court accomplished a breakthrough for women's human rights in international law by defining sexual violence against women such as rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, and other sexual assaults as crimes against humanity.

Thus, international laws on women's human rights and wartime sexual violence made great strides in the 1990s, and many reports addressing the 'comfort women' issue were written amid this context. Afterwards, the 'comfort women' issue was addressed as an important topic in Coomaraswamy's report submitted to UNCHR in 1996, the McDougall Report4 adopted by the UN SCPPHR in 1998, the ILO report, the annual report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), and so on. Through this process, the notion of 'comfort women' was conceptualized as a 'sex slave', while the notion of comfort stations was conceptualized as a 'rape center'. The McDougall Report particularly contains comprehensive subjects ranging from the problem of the absence of punishment for the perpetrators of grave human rights violations to the punishment of those responsible for the crime. Based on these reports, many international human rights organizations have thus far adopted numerous recommendations urging the Japanese government to take responsible attitudes.

This article will continue in Part 2.

Related contents

-

- The supranational nature of the 'comfort women' issue and the ‘glocalization’ of memories, Part 2

-

Written by Shin Ki-young, Professor at Ochanomizu University, Japan

- Writer Shin Ki-young

-

Professor at Ochanomizu University, Japan

kiyoungshin11@gmail.com