A “Comfort Woman” Who Has Yet to Return Home, a Memory That Has Yet to Be Mourned: The Name Bae Bong-gi

The Earliest Official Witness to the Japanese Military’s “Comfort Woman” System

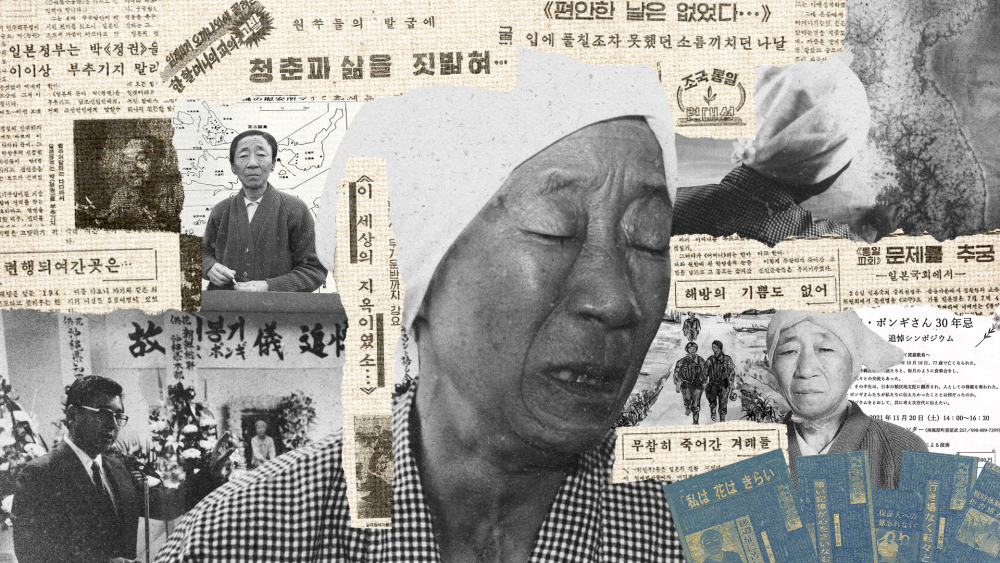

In the autumn of 1991, in a shabby boarding house in Okinawa, a woman was found dead—alone. Her name was Bae Bong-gi. Born in colonial Korea, Bae was taken to the battlefield and forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese military as a “Comfort Woman.” After the war, she remained in Okinawa without citizenship and lived out the rest of her life there, never returning to her homeland.

In 1975, she applied for special residency status from the Japanese government, disclosing that she had been brought to Okinawa as a “Comfort Woman.” This remains the earliest officially recorded testimony from a survivor of the Japanese military’s “Comfort Women” system—preceding Kim Hak-sun’s testimony in 1991 that marked the beginning of the “Comfort Women” movement by sixteen years. Yet Bae’s name was not remembered as the “first” for long.

Born in 1914 in Sillyewon, Yesan-gun, Chungcheongnam-do Province, Bae was the second daughter of a farmhand father and a mother who worked as a day laborer. As a young girl, she was sold into servitude to her husband’s family. After her marriage ended in failure, she supported herself by working as a nanny. She later settled in Hamheung, Hamgyeongnam-do Province, where she worked as a day laborer until 1943, when she was approached by “female recruiters” offering a job that would allow her to “earn money with ease.” From Heungnam Station, she traveled through Gyeongseong, Busan, Shimonoseki, Moji, Kagoshima, and finally arrived on Tokashiki Island in Okinawa. The job turned out to be that of a “Comfort Woman.”

Okinawa was the only part of the Japanese mainland to experience ground warfare at the end of World War II. Bae barely survived its horrors. But her suffering did not end with the war. Under U.S. military rule, she was classified as a “stateless Korean,” and when Okinawa was returned to Japan in 1972, she became an “illegal alien.” In order to secure legal residency, she had no choice but to disclose her past as a “Comfort Woman.” Although her testimony was the earliest one from “Comfort Women” survivors, it remained overlooked in Korea for many years. Her name was largely absent from the history of the “Comfort Women” movement.

The name that had quietly faded into obscurity in Korean society reemerged only at the very end of her life. The significance of her death extended far beyond that of an individual loss. When news of her passing reached the public, it sparked a conflict between two major Korean organizations in Japan—the Korean Residents Union in Japan (Mindan) and the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon)—over where her remains should be buried and who had the right to organize her funeral rites. Whose “death” was this? Where should she be laid to rest? Who has the authority to “speak” on her behalf? This contest over Bae’s remains was not merely a matter of funeral arrangements. It revealed the enduring legacies of colonialism and the Cold War that had shaped her entire life. And it raises still deeper questions: How do we remember the past? How do we mourn the dead?

“Whose” Remains? The Dispute Between the Mindan and Chongryon Over the Ownership of Bae Bong-gi’s Ashes

A powerful wave of change swept across East Asia in the late 1980s. The global thawing of the Cold War—accelerated by Gorbachev’s rise to power and the Soviet Union’s reformist policies in 1985—and South Korea’s democratization in 1987 brought renewed attention to the issue of Japan’s military “Comfort Women,” reframing it within the language of civil movements. One particularly pivotal moment was the international seminar Women and Tourism Culture, organized in 1988 by the Korea Church Women United (KCWU), which had campaigned against the “gisaeng tourism” industry and the authoritarian Yushin regime since the 1970s. The so-called “gisaeng tourism” of that era, aggressively marketed to Japanese men by the Korean government, was essentially a form of state-sponsored sex trafficking. At the seminar, Ewha Womans University professor Yun Chung-ok—who would later become the first co-chair of the Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (Jeongdaehyeop)—presented the findings of a long-term field study titled “The Issue of the Jeongsindae and Our Duties.” The report sparked public outcry and led to the formation of the KCWU’s Research Committee on the Jeongsindae, as well as a series of influential feature articles published in the Hankyoreh newspaper in January 1990.

This marked a turning point in the trajectory of Korea’s women’s movement. In November 1990, a coalition of women’s organizations founded the Jeongdaehyeop, which played a decisive role in bringing the issue of “Comfort Women” into social discourse. Then, on August 14, 1991, a survivor named Kim Hak-sun made her first public testimony about her experience as a “Comfort Woman.” Her testimony, which condemned the atrocities of Japanese imperialism, laid the groundwork for global solidarity.

Bae Bong-gi, it seems, was not unaware of these shifts. According to a 2012 interview with Kim Hyeon-ok, a Chongryon activist who had cared for her, when asked during the 1988 Seoul Olympics whether she wished to visit her hometown in South Korea, Bae replied: “I would like to, but I can’t—because there’s a U.S. military base in my hometown.” She also reportedly expressed interest in Lim Su-gyeong, the South Korean student who attended the 1989 World Festival of Youth and Students in North Korea, and followed the diplomatic talks between North Korea and Japan that began in 1990 with hope.

Yet, when Bae died alone in Okinawa on October 18, 1991, her death received scant attention in the South Korean media. Her obituary, brought back by Jeongdaehyeop Co-Chair Yun Chung-ok after traveling to Okinawa upon hearing the news, was reduced to a single line in the Hankyoreh.

Public attention, instead, fixated on her remains, not her life. Several days before the first anniversary of her passing, the Chongryon announced its intention to keep Bae’s ashes in Okinawa, interpreting her words—“I will return to a unified Korea without foreign troops”—as her final wish. On the other side, a nephew from the Mindan stepped forward, stating his intention to bring his aunt’s ashes back to her hometown. The dispute between the two factions ultimately escalated into a legal battle.

Since Bae was found five days after her death, it remains unknown where she truly wished to be buried. Yet fragments of her voice survive—in the 1987 memoir The Red-Tiled House, a 1989 interview, the 1991 documentary Song of Arirang, and the 2017 film Silence. These glimpses suggest that her emotional struggle was not simply a matter of choosing which one nation she wished to belong to:

"I visited my hometown once, but my home was no longer there... I felt so lonely."

"I want to visit again, but there’s no one left I know—it would make me feel even lonelier.

Such words reflect the complex and often contradictory feelings felt by those who no longer feel safe or welcome in their place of origin when they contemplate returning home.

The ideological contest over Bae’s death, then, worked to overwrite her own words. Postcolonial feminist scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak famously posed the question, “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” highlighting how the absence of interpretive frameworks renders the voices of the marginalized unheard and incomprehensible. In Bae’s case, aside from the voice preserved in recordings, her words were co-opted—reframed and reinterpreted through competing narratives. The Mindan claimed her as “a woman who wished to return to her homeland,” while the Chongryon presented her as “a woman who rejected a divided homeland.” In both political memories, she was silenced once more.

A “Comfort Woman” Who Never Returned Home and South Korean Society That Turned a Cold Shoulder

The emotional depth and complex political circumstances surrounding Bae’s death were largely dissolved in the indifference shown by South Korean society. The competing acts of “speaking on her behalf” carried out by the Mindan and Chongryon served only to obscure public interest in the life she had led and the emotions she may have experienced at its end. South Korean society, in effect, silently acquiesced to this politics of erasure.

To be sure, in 1991 the Mindan and the South Korean government were not aligned in their positions. South Korea was pursuing a new diplomatic course amid the rapidly shifting dynamics of the post-Cold War world. Having already normalized relations with the Soviet Union, the country was preparing to establish diplomatic ties with China. The Special Presidential Declaration for National Self-Esteem, Unification, and Prosperity announced by President Roh Tae-woo in 1988—also known as the July 7 Declaration—and the inter-Korean Prime Ministers’ talks in the same year had fostered a mood of cautious reconciliation. However, tensions with Japan, which sought to expand its influence in the region, remained sensitive, while North Korea was entering a period of deep economic hardship and diplomatic isolation amid the collapse of global socialism.

Against this backdrop, North Korea and Japan conducted eight rounds of normalization talks, beginning in January 1991 and continuing over the next two years. Notably, during the sixth and seventh rounds in 1992, North Korea demanded an official apology and reparations from Japan over the issue of military “Comfort Women.” In other words, around Bae’s passing and its first anniversary, the “Comfort Women” issue had emerged as a key topic in North Korea–Japan diplomatic engagement.

The Chongryon sought to leverage this momentum, while the Mindan tried to curb it. From this perspective, the Mindan’s legal claim to Bae’s ashes—filed through her nephew—may be understood less as a familial duty than as a political maneuver. Yet South Korean society and its government remained largely silent. Little attention was paid to Bae’s death or the legal dispute surrounding it, echoing the silence that had accompanied the first reports of her life in 1975.

However, the silences of 1975 and 1991 were fundamentally different. The 1970s were still marked by a hardline Cold War atmosphere, where any public discussion of Chongryon-related matters was practically taboo in South Korea. By contrast, 1991 was a time of democratization and de–Cold War transformation in society. The simultaneous admission of both Koreas into the United Nations, the signing of the South-North Basic Agreement, and the Joint Declaration of the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula all reflected a prevailing tone of inter-Korean reconciliation—one that demanded a strategic avoidance of politically sensitive topics. Bae’s death, in this context, was deliberately and ‘quietly’ downplayed so as not to undermine the spirit of rapprochement.

From her perspective, however, this silence amounted to yet another exclusion. To erase the life of a woman drafted into imperial military sexual slavery and who died in exile, in the name of reconciliation, was another form of Cold War ideology under a different guise.

By this time, the issue of Japanese military “Comfort Women” was rising rapidly on South Korea’s public agenda. A series of international conferences titled Peace in Asia and Women’s Role, held in Japan, South Korea, and North Korea between 1991 and 1993, illustrated the growing potential for transnational solidarity. The third round of the conference, hosted by North Korea from September 1 to 6, 1992, drew considerable attention—even from the South Korean mainstream media. Women from both Koreas, as well as from Japan, the United States, and Germany, gathered to address the “Comfort Women” issue, which North Korea redefined as an issue of the entire Korean people that required inter-Korean responses. Japanese participants were positioned as allies of solidarity— simultaneously as citizens of the perpetrator nation and as victims of imperialist society themselves. Yet even within this space of shared activism, the political contest over the memory of women like Bae—those who “haven’t yet returned”—remained unaddressed.

Meanwhile, on December 6 of that same year, the day marking the 49th day memorial of Bae’s death, Kim Hak-sun became the first surviving victim to file a civil suit for damages at the Tokyo District Court. On the same day, the history of “Comfort Women” was being memorialized in starkly different ways in Japan and South Korea. The juxtaposition of these two events raises fundamental questions about the narratives we have centered on and how those choices have shaped our memory.

In retrospect, the South Korean “Comfort Women” movement has primarily framed memory within the paradigm of inter-state relations. As a result, it has struggled to recognize those who fell outside these national borders and quietly disappeared. Bae’s death lay precisely in that space in between. Her life and death were shaped by the orders of imperialism, the Cold War, and national division. Neither social movements nor official responses at the time were able to fully grasp the complexity and emotional nuance at the heart of the issue.

Even now, more than twenty years later, it remains difficult to answer: how should we remember, or mourn, such layered emotions? In this sense, Bae is still someone who has not yet “come home.”

Remembrance or Repossession?

Her remains now lie before us once again. On March 10, 2025, the civic group Bae Bong-gi’s Peace posted photos on Instagram announcing that her urn had been damaged during transport from Okinawa to South Korea, and that her ashes had been scattered and mixed with the soil. These images bring back the same unresolved question: Where should she be buried, and whose memory will shape the narrative of her life?

Bae Bong-gi’s Peace has been organizing public gatherings to call for her remains to be interred at the National Mang-Hyang Cemetery, appealing for government cooperation under the name of “Bae Bong-gi, the first witness to the Japanese military’s Comfort Women system.” I do not deny that there is meaning in her name being invoked once more. But the emotions I feel are complicated.

The title of “first witness” can be a significant recognition. Yet I am cautious of how such a title may once again confine her life within a nationalist framework. More crucially, should we not reflect more deeply on why her testimony remained unheard for so long? Her words were not absent—they existed—but it was colonialism, the Cold War, and state-centered memory regimes that persistently rendered them inaudible. If these structures are left unexamined, then commemorating her once more “in the name of the state” risks becoming another act of institutionalized mourning—an act that reabsorbs memory into the operations of power, and obscures the intellectual labor and hard work that sustained that memory until now.

For me, the name Bae Bong-gi has long stood as a symbolic site where colonialism, the Cold War, and violence of states and patriarchy converge. I have aspired to understand, as fully as possible, the complexity of emotions she must have carried—longing for a homeland she returned to only in dreams, never in reality. That is why I have asked myself: Could mourning take a different form? Could it not be possible for those who remember her to care for her ashes collectively, rather than for a single group or state to claim possession of them? Might there be a way for her neighbors in Okinawa and her compatriots in South Korea to honor her together, transcending the adversarial structure that divides the two states?

Perhaps it is not too late. To re-remember Bae Bong-gi must go beyond simply conferring upon her a new title as “the first state-recognized witness.” It must begin by asking why her voice was silenced and by confronting the very structures that suppressed it—colonial rule, Cold War division, and the nationalist framework that has shaped the “Comfort Women” discourse. True mourning begins when we go beyond systems and institutions. If we are to remember her, then that memory must open onto a new narrative, a new form of solidarity, and a new ethics for our time.

Footnotes

This article is adapted from Chapter Five, “Contested Death: A Voice Erased,” of the author’s academic paper “Cold War and ‘Comfort Women’: Bae Bong-gi’s Forgotten Life and Contested Death,” originally published in the Journal of Korean Women’s Studies (Vol. 37, No. 2, 2021, doi: 10.30719/JKWS.2021.06.37.2.203). It has been revised in alignment with the purpose of the webzine Kyeol. A further expanded version of this essay was later published under the title “Bae Bong-gi’s Forgotten Life and Contested Death” in the book The “Comfort Women” and the Responsibility to Debate More: Beyond the Hostile Coexistence of Nationalism and Outrageous Political Remarks (ed. Kim Eun-sil, Seoul: Humanist, 2024).

- ^ https://www.facebook.com/baebonggi.peace

Related contents

-

- 배봉기 씨가 오키나와에서 걸어온 전후(戦後)

-

배봉기 씨는 이 세상에 없다. 하지만 지금도 많은 오키나와 사람들의 마음속에 배봉기 씨는 살아 숨 쉬고 계신다.

-

- The Story of Bae Bong-gi – “We luckily managed to survive amid that war.”

-

In her book <The House with a Red Tile Roof - The Story of Korean Women Who Became the Japanese Military "Comfort Women"> which was translated into Korean in 2014, Kawata Fumiko vividly yet calmly unraveled the testimony of Bae Bong-gi, one of the Korean "Comfort Women" who was taken to Okinawa. Based on the testimonies and data collected from Okinawa residents, Japanese soldiers, as well as Bae Bong-gi, this article describes the detailed circumstances experienced by Bae Bong-gi and the “Comfort Women” surrounding the U.S. military’s air raids that took place on the Kerama Islands, Okinawa.

-

- 오키나와 사람들과 '위안부' - 기억을 공간화하며 '위안부'의 삶을 증언하는 사람들 〈상〉

-

이 글은 한국과 일본 사회에서 어느 누구도 첫 번째 '위안부'로 기억하지 못했던 배봉기를 기억하는 오키나와 사람들의 이야기이다. 이들은 '위안부' 문제를 어떻게 기억하고 전하려 했을까.

-

- Remembering Bae Bong-gi

-

she said, with tears streaming down her cheeks, when a Japanese journalist suggested they go back and visit her old home together. Away for so long from her hometown in South Chungcheong Province – a place which she could now only dream about.

- Writer Kim Shin Hyun-gyung

-

Kim Shin received her Ph.D. in Women’s Studies from Ewha Womans University, with a dissertation on the transformation of the Korean entertainment industry and actresses as gendered image commodities. Her subsequent research has focused on the media industry, gendered labor, and the mobilization of women’s bodies and sexuality within the postcolonial Cold War order. She has continued her academic journey as a postdoctoral fellow at the Graduate School of East Asian Studies, then as a research professor of the Institute of Korean Studies at the Free University of Berlin, and currently as an assistant professor at the College of General Education, Seoul Women’s University. Her article “Cold War and ‘Comfort Women’: Bae Bong-gi’s Forgotten Life and Contested Death” received the Best Article Award from the Korean Association of Women’s Studies in 2022. In 2023, the Seoul Journal of Japanese Studies selected her article “How Recent Films Portraying ‘Comfort Women’ Represent the Cold War Regime: An Analysis of the Korean Films Herstory and I Can Speak” as the Best Article.

![[Photo 1] Bae Bong-gi in the late 1970s. A scene from the film Okinawa No Harumoni (directed by Yamatani Tetsuo, 1979).](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%EB%B0%B0%EB%B4%89%EA%B8%B01.png?itok=vw25-8JF)

![[Photo 2] Memorial service for Bae Bong-gi (December 6, 1991 / Courtesy of Kim Hyun-ok). [Photo 2] Memorial service for Bae Bong-gi (December 6, 1991 / Courtesy of Kim Hyun-ok).](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%EB%B0%B0%EB%B4%89%EA%B8%B0%ED%95%A0%EB%A8%B8%EB%8B%88%EC%9D%98%20%EC%B6%94%EB%8F%84%EC%8B%9D%20%281991.12.6%29.jpg?itok=jcNHbuD3)

![[Photo 3] View of the burial site where Bae Bong-gi is laid to rest. The site is located in her hometown, Sillyewon-ri, Yesan-eup, Yesan County, Chungcheongnam-do. (Photo taken on April 30, 2025)](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%5B%EC%82%AC%EC%A7%843%5D%20%EB%B0%B0%EB%B4%89%EA%B8%B0%20%ED%95%A0%EB%A8%B8%EB%8B%88%EA%B0%80%20%EC%95%88%EC%B9%98%EB%90%9C%20%EB%AC%98%EC%97%AD%20%EC%A0%84%EA%B2%BD.jpg?itok=jUIDBdJ-)