Why the “Statue of Peace” Exhibition Is an Act of Practice:

The Power of “Civic Solidarity” that Finally Realized Japan’s “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition”

The “Statue of Peace” was first erected in Korea in 2011 to commemorate the 1,000th “Wednesday Demonstration.” Since then, more than 80 statues have been installed across Korea, with additional statues erected in countries such as the United States and Germany. However, Japan—the country directly involved—has yet to install a single statue. In Japan, the statue is typically displayed only in the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition,” an art exhibition dedicated to works excluded from public display for political reasons.

In Japan, there has been ongoing criticism that the Statue of Peace limits the representation of wartime sexual violence victims to the image of a “young girl.” Right-wing groups and the Japanese government have also labeled it the “‘Comfort Woman’ statue” and have used every means to obstruct the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition” whenever it was held. Despite this, efforts to display the statue have persisted, with exhibitions planned and held across various regions. Numerous volunteers and lawyers have participated, filing legal appeals and working to protect these exhibitions. What, then, has sustained these ongoing efforts?

Japan’s Statue of Peace Exhibitions Repeatedly Thwarted by Disruptions and Threats

In Japan, the “Statue of Peace” has become the target of intense hatred. Right-wing supporters have repeatedly engaged in acts of direct vandalism, including “driving stakes into the statue,” “placing paper bags over its head,” and physically “kicking it.” Some lawmakers and prominent novelists have even made grotesque threats, such as talking about “blowing it up” or “dousing it with semen.” These acts seem to be aimed at hindering the internationalization of the “Comfort Women” issue and preventing the portrayal of the victims as “young girls.”

Then, how did the exhibition of the “Statue of Peace” come about in Japan? Its origins can be traced back to 2012. A photographer from Nagoya, Ahn Sehong, had been documenting the lives of 12 former “Comfort Women” victims. He planned to hold a photo exhibition titled “Layer by Layer: Surviving Korean ‘Comfort Women’ Left Behind in China” at the Nikon Salon in Tokyo. Although the exhibition had been approved a year in advance, the situation took a sudden turn just a month before its opening. An article in “Asahi Shimbun” introducing the exhibition caught the attention of right-wing groups, sparking a wave of protests. Although Ahn filed for an injunction and secured the legal right to use the venue, the exhibition was ultimately canceled just three days before it was set to open.

Two months later, a similar incident took place. At the 18th JAALA (Japan, Asian, African, Latin-American Artist Association) International Art Exchange Exhibition, hosted by JAALA and held at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, a miniature of the Statue of Peace and the oil painting “Comfort Women!” by artist Park Yun-bin were displayed. However, on the fourth day of the exhibition, the museum removed the artworks without prior notice or consent. Unlike the case of Ahn Sehong’s exhibition, however, this incident received no media coverage.

Upon encountering this series of events, media artist Jun Oenoki criticized the disruption of exhibitions by projecting the rejected artworks onto the walls of the museum. In 2014, as a protest against repeated infringements on freedom of expression, the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo Executive Committee” was established. The following year, in 2015, the “Statue of Peace” was featured in the committee’s first exhibition at Gallery Furuto in Tokyo. According to Yuka Okamoto, who led the committee, the committee concluded that a statue made of fiberglass-reinforced plastic (FRP) would be suitable for exhibition in Japan and commissioned the work from the husband-and-wife artist duo Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung, the creators of the Statue of Peace. The artists readily accepted and, after learning of the committee’s limited budget, personally helped cover the transportation costs. To bring the large statue into Japan, it was divided into three parts and painstakingly reassembled and repainted on-site. Before leaving Japan after the exhibition, the artists signed the back of the statue with the messages: “This statue should stay in Japan” and “We leave it in Japan.” In this way, the “Statue of Peace” came to have a permanent presence in Japan. Today, it is carefully stored in a small hut belonging to a theater troupe in Tokyo and is available for free loan. It has also been used for theatrical performances and film productions.

To Bring to Light the Statue of Peace “Forced into Disappearance”

The “Statue of Peace” gained widespread public attention when it was included in the exhibition “After ‘Freedom of Expression?’” at Aichi Triennale 2019 (hereafter AITRI 2019). Held every three years in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, AITRI is Japan’s largest international art festival, drawing more than 250,000 monthly visitors. When news spread that the statue would be featured in the exhibition, it sparked controversy: right-wing groups issued threats, and some politicians voiced strong opposition. Consequently, the exhibition was suspended just three days after opening. The following month, Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs announced it would withhold the full subsidy of approximately 78 million yen that had been allocated to the Triennale (a reduced amount was later granted). In response to this suppression of freedom of expression, participating artists protested by sealing their works, refusing to exhibit, and issuing public statements in solidarity.

Subsequently, as the relationship between the city and the prefecture deteriorated over the subsidy, Nagoya Mayor Takashi Kawamura, along with right-wing intellectuals such as Takasu Clinic Director Katsuya Takasu, Naoki Hyakuta, Tsuneyasu Takeda, and Kaori Arimoto, launched a recall petition campaign[1]against Aichi Prefecture Governor Hideaki Ōmura. However, in 2021, it was reported through the media that an investigation by the election commission had found 83.2% of the collected signatures to be forged or otherwise fraudulent.

So, what happened to the Statue of Peace, which had been “forced into disappearance” from the “After ‘Freedom of Expression?’” exhibition? In many ways, it marked a new beginning. In response to requests from those who had been unable to see the statue at AITRI 2019, independent groups began organizing exhibitions across Japan. Starting in Tokyo, related organizations joined forces in solidarity to host exhibitions in various regions nationwide. Although each planned venue faced protests, pressure, and disruptions from right-wing groups, citizens’ efforts secured the right to exhibit the statue in cities like Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka.

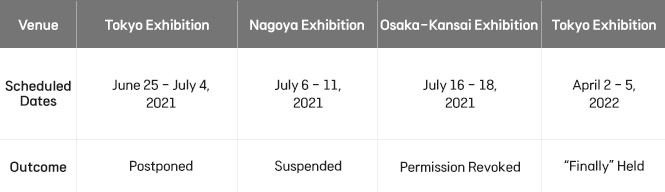

▶ Postponed Tokyo Exhibition

The first exhibition of the Statue of Peace was scheduled to take place in Tokyo, running from June 25 to July 4, 2021, at the Session House Garden Gallery in Shinjuku. The “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo” had announced its opening and begun accepting viewing applications. However, due to persistent interference and street propaganda from right-wing groups, the gallery director reversed the initial decision, citing concerns about the exhibition’s potential negative impact on the neighborhood. Despite strong citizen support and urgent efforts to secure a new venue, all attempts ultimately failed, leading to the exhibition’s cancellation.

▶ Nagoya Exhibition Suspended After Temporary Closure

Following the “AITRI 2019 incident,” a group called “Aichi Association for Continuing ‘Freedom of Expression?’” organized the exhibition titled “Our own After ‘Freedom of Expression?’” at the Nagoya Citizens’ Gallery Sakae, scheduled for January 2021. Anticipating interference, the organizers took careful precautions, consulting with both facility administrators and the police. However, when the exhibition was officially announced for July 6–11, street protests and direct threats against the organizers intensified. On July 8, a suspicious package was delivered to the gallery, prompting an evacuation order for staff and a lawyer. When the package was opened under police supervision, a firework-like device exploded. Despite attempts to negotiate, the gallery management and local authorities refused to cooperate and extended the closure of the gallery. Ultimately, the organizers had no choice but to cancel the exhibition.

▶ Kansai Exhibition in Osaka—Permission Revoked

The Osaka Executive Committee, which took over the artworks from the Nagoya exhibition, planned to hold the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Kansai” at L-Osaka (Osaka Prefectural Labor Center) from July 16 to 18. However, on June 25, the venue revoked its approval, citing “safety concerns.” In response, the committee filed a lawsuit with the Osaka District Court demanding the withdrawal of the cancellation. On July 9, the court ruled in favor of the committee. Subsequent appeals to the High Court and the Supreme Court were also dismissed, thereby eliminating any grounds for obstructing the exhibition in public facilities.

▶ Tokyo Exhibition Finally Held

Based on the court rulings on the Osaka exhibition, which provided the legal grounds for hosting the exhibition in public facilities, the Executive Committee launched a crowdfunding campaign one month prior to the event. The campaign successfully raised 3,412,900 yen from 462 supporters. Finally, the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo 2022” (hereafter Tokyo Exhibition) was held from April 2 to 5, 2022, at the Kunitachi Community Arts Center.

Defend the Exhibition! Inside and Outside the Intense Tokyo Exhibition

As a staff member who actively participated in the Tokyo Exhibition, I had the opportunity to experience many things as an insider. One of the most meticulously planned tasks was to safeguard the exhibition itself, referred to as “defense.” Each day, approximately 40 volunteers, totaling around 240 throughout the exhibition period, along with 70 lawyers, participated in implementing a detailed security plan that included shift work and confirming legal measures. Coordination with the police was also carefully undertaken.

As expected! During the exhibition, around 40 right-wing groups gathered to stage street propaganda campaigns, shouting through loudspeakers: “Are you fools to exhibit a fabricated story about the military ‘Comfort Women’ that never existed, turning the Statue of Peace into a symbol and calling it art? Beyond these street demonstrations, they disrupted the display of the Statue of Peace through various means: some filmed the exhibition without permission, others read protest statements aloud in front of the venue and delivered them to the executive committee members, and some even purchased tickets to enter the gallery. In addition, right-wing individuals took videos of the exhibition and uploaded them to YouTube and Twitter. The defense team, who were usually active in countering hate speech, carefully monitored and shared information to identify these “persons of concern.” Even outside the venue, they collaborated with local “counter-movement”[2] groups to track the movements of such individuals whenever posts surfaced online, such as “○○ is heading to the Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition.”

As right-wing protests intensified with hate speech, counter-movements typically escalated in response. However, such tensions were rarely seen at the Tokyo Exhibition. Even at the Kansai Exhibition, the mannequin flash mob performance was carried out as a quiet form of counter-movement. The volunteers defending the Tokyo Exhibition adopted a strict non-engagement policy, refusing to respond to any right-wing street propaganda or provocations involving hate speech. Instead, what the Executive Committee prioritized for the Tokyo Exhibition was building connections with the local civic activist network in Kunitachi, the host city. Leveraging their networks, the committee enlisted Kunitachi residents willing to support the exhibition and, together with them, launched the “Association for the Realization of Art Exhibitions.” This initiative helped establish a coordinated “defense system” based on the solidarity of the police, venue staff, committee members, and local citizens, ensuring the exhibition could be held safely.

Meanwhile, the public security police were also a subject of vigilance. We discovered that the officers who had initially coordinated with us were actually monitoring the exhibition organizers, which made us realize that we needed to protect ourselves. On the first day of the exhibition, a plainclothes officer posing as a staff member unlawfully entered the gallery, prompting actual staff to intervene. Similar incidents continued to occur thereafter. On the morning of the second day, information was shared among all staff that “public security officers and police were spotted wearing Kunitachi City Hall badges.” Warnings were circulated, emphasizing that “the police are not on our side, so exercise caution.” In addition, concerns were raised that three of the 18 security cameras installed by the facility belonged to the police. After consulting with the Board of Education and the police in the presence of a lawyer, significant concerns were confirmed. It was agreed that the footage from the three police-operated cameras would be deleted in the presence of representatives from the Art Center and the city’s Board of Education.

Another Name for the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition”: The Solidarity, Goodwill, and Passion of Citizen Volunteers

Then, who were the individuals who gathered as volunteers? The core members responsible for defense and the lawyers were executive committee members, experienced individuals, or experts, and thus preparations, including advance procedures with the police, were carried out with great precision. The rest of the volunteers were mainly introduced through personal networks—trusted individuals recommended by reliable committee members. Since the preparation meetings were held via the video conferencing platform Zoom, even basic information such as people’s names or occupations was unknown.

The exhibition site was constantly bustling with activity. In hindsight, the volunteers included a diverse range of people: local civic activists, students, Zainichi Koreans, as well as homeless people and the elderly. As a result, the operation of the venue was, to put it humorously, “utter chaos.” Despite many challenges, the lunchboxes delivered daily from a restaurant run by a local Zainichi Korean were always delicious. They didn’t have to be “Korean food,” but those meals served as a subtle reminder that this exhibition was, after all, an art event centered around the “Statue of Peace.”

The Tokyo Exhibition, along with all previous regional editions of the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition,” was not organized by a national entity but operated through a collective model. Volunteers gathered and dispersed in a fluid, decentralized mannercoming together out of goodwill and passion and working in solidarity, often without even knowing one another’s names or professions. The exhibition venues, too, were public spaces, not owned by any individual or group. Consequently, a culture of continuously updating information and engaging in ongoing discussions naturally emerged whenever problems arose in negotiations or operations.

The Significance of Exhibiting the “Statue of Peace”

What significance does exhibiting the “Statue of Peace” hold? First and foremost, as Professor Mooam Hyun of Hokkaido University points out in East Asia in Post-Imperial Japan: Discourse, Representation, Memory (Seidosha, 2022), “the statue does not represent inter-state confrontation but stands at the crossroads of civic solidarity resisting colonialism and wartime sexual violence.” This practice is carried out within the “intimate sphere”[3] of movement culture—characterized by volunteerism, a DIY (Do It Yourself) spirit, and a collective method. Through the cyclical process of assembling, acting, and disbanding, citizens of the perpetrator country respond as partners in addressing the “Comfort Women” issue.

Secondly, this practice has expanded the issue to the public space. For some time, the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition” was held in private galleries, but it is now being held in public facilities. Of course, securing permission remains difficult due to security concerns, particularly with the potential for right-wing interference. However, in Japan, where it is challenging to address the issue of “Comfort Women” in the public space or through public media, this practice represents an important struggle to bring the issue into the public space. It is also noteworthy as an indication of the expansion of the Japanese civil movement into the public space.

Thirdly, this practice has renewed awareness of the importance of “movement.” In the past, I felt ashamed that the Statue of Peace could not be permanently erected in Japan. However, after becoming involved in the movement to exhibit the statue, my perspective changed. In the context of Japanese society, I now believe it is more meaningful for the statue to “move” across different regions through exhibitions, rather than being permanently installed in a single location. These regional exhibitions are not conducted as part of a nationwide tour led by the Tokyo Executive Committee. Rather, each time an exhibition is held, a new local executive committee is formed, and the event is organized through solidarity with local civic movements and volunteers. In this process, citizens who advocate for freedom of expression and peace confront the prejudice, hate, and violence perpetrated by government authorities, the police, and right-wing groups. In this way, the exhibition of the Statue of Peace in Japan has become a practice through which the intimate sphere of Korea–Japan solidarity on the “Comfort Women” issue extends into the public sphere (公共圏)[4], as the Statue of Peace, which symbolizes the memory of victimization, moves from place to place, broadening the “sites of memory.”

Footnotes

- ^ Recall petition campaign: Key figures active at the time included lawyer Yuji Nakatani, co-chair of the “Aichi Association for Continuing ‘Freedom of Expression?’” and Yuka Okamoto, co-chair of the Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo Executive Committee.

- ^ Counter-movement: Also referred to as the “Counters Movement,” this is a grassroots civic initiative that emerged in Japan in the early 2000s to oppose escalating hate speech and racism. It played a leading role in the enactment of Japan’s Hate Speech Elimination Act.

- ^ Intimate sphere: This term refers to a space of love and mutual support, including forms of solidarity among directly involved individuals.

- ^ Public sphere: While academic discourse differentiates among national, formal, and civic public spheres, the term here refers to a space where individuals exchange opinions on matters of shared concern and form political will. Specifically, it denotes a dialogic space within civil society—independent of state or market control, such as the media—where conversation unfolds voluntarily, free from coercion or exclusion.

Related contents

-

- The Statue of Peace Arrives in Stintino, Italy, Carrying a Message of Human Rights and Peace

-

A story of Stintino’s commitment to justice and humanity, its focus on raising awareness and finding solutions to end violence against women, and the arrival of the Statue of Peace in the town.

-

- 소녀상만사 새옹지마 -독일 '평화의 소녀상' 이야기- 〈상〉

-

독일의 소녀상은 어떤 과정을 거쳐 건립되었을까. 이 글은 독일에서 처음으로 소녀상 건립이 공론화된 2016년부터 지금, 여기 이 쉼표 지점까지의 이야기다.

-

- 소녀상만사 새옹지마 -독일 '평화의 소녀상' 이야기- 〈하〉

-

독일의 소녀상은 어떤 과정을 거쳐 건립되었을까. 이 글은 독일에서 처음으로 소녀상 건립이 공론화된 2016년부터 지금, 여기 이 쉼표 지점까지의 이야기다.

- Writer Kohei Kurahashi (倉橋耕平)

-

Kohei Kurahashi is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Letters at Soka University. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology, and his research focuses are media culture and gender studies. His publications include Historical Revisionism and Subculture (Seikyusha, 2018), and he has co-authored works such as What is the Internet Right Wing? (Seikyusha, 2019), Political Sociology of Japan-Korea Solidarity (Seidosha, 2023), and The Age of Global Narratives and Historical Representations (Seikyusha, 2024). He also served as the supervising editor for the Japanese edition of Leo Chin’s Anti-Japan (Jinbun Shoin, 2021).

![[Photo 1] The “Statue of Peace” on display at the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo” for the first time in over a decade (Photo courtesy of Kohei Kurahashi) [Photo 1] The “Statue of Peace” on display at the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo” for the first time in over a decade (Photo courtesy of Kohei Kurahashi)](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%E1%84%89%E1%85%A1%E1%84%8C%E1%85%B5%E1%86%AB1_%E1%84%8F%E1%85%AE%E1%84%85%E1%85%A1%E1%84%92%E1%85%A1%E1%84%89%E1%85%B5%E1%84%8F%E1%85%A9%E1%84%92%E1%85%A6%E1%84%8B%E1%85%B5.jpeg?itok=XdTQik85)

![[Photo 2] Web poster for the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo” [Photo 2] Web poster for the “Non-Freedom of Expression Exhibition Tokyo”](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%E1%84%89%E1%85%A1%E1%84%8C%E1%85%B5%E1%86%AB2_%E1%84%8F%E1%85%AE%E1%84%85%E1%85%A1%E1%84%92%E1%85%A1%E1%84%89%E1%85%B5%E1%84%8F%E1%85%A9%E1%84%92%E1%85%A6%E1%84%8B%E1%85%B5.png?itok=ILg7OVkp)

![[Photo 4] Screenshot from a YouTube livestream showing a disruptive protest by the right-wing political party Kunimori. (Photo courtesy of Kohei Kurahashi) [Photo 4] Screenshot from a YouTube livestream showing a disruptive protest by the right-wing political party Kunimori. (Photo courtesy of Kohei Kurahashi)](https://kyeol.kr/sites/default/files/styles/article_embed/public/%E1%84%89%E1%85%A1%E1%84%8C%E1%85%B5%E1%86%AB4_%E1%84%8F%E1%85%AE%E1%84%85%E1%85%A1%E1%84%92%E1%85%A1%E1%84%89%E1%85%B5%E1%84%8F%E1%85%A9%E1%84%92%E1%85%A6%E1%84%8B%E1%85%B5.png?itok=aa0biz8g)