The term “Comfort Women” is locked in quotation marks, which was arranged for sprucing up the Japanese army’s sexual mobilization of Korean women during World War II and adding reservations to the euphemism employed to conceal the sufferings of victims. The early uses of “Comfort Women” are found in official documents prepared by the Japanese Army and police in 1938.[1] The term is sanitizing language that ensures war is conducted in a business-like manner and “makes it possible to name injury without imagining it every day.”[2] Thus, the violence of Japanese imperialism and its wartime administration, which supplied women’s sexuality as war materials, becomes invisible within the gender-role stereotype where a woman is a being to comfort a man.

Reframing the issue of sexual abuse “from the shame of the victim to the crime of the perpetrator,” which was attributed to the women’s movement, allowed victimization to be socially recognized and survivors to speak out. Meanwhile, in the name of tradition, wartime rape was connived as customary practice and was regarded as a disgrace to the victim, so no statutory punishment was carried out. However, genocidal rape committed during the breakup of Yugoslavia and ensuing ethnic conflicts in the early 1990s served as a turning point in wartime sexual violence. In the wake of the war, the international judicial provisions prohibiting “sex slavery” emerged, identifying wartime rape as a systematic war crime rather than an accidental, individual “incident.”[3]

Just in time, the Working Group of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights posed a problem that “‘Comfort Women’ are sexual slaves” in 1992, and the Sub-Commission on the Prevention of the Discrimination and Protection of Minorities adopted a resolution on wartime slavery in August 1993, bringing the issue of the Japanese military “Comfort Women” into the international public arena.[4]

The Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan and civic organizations in Japan and Asia engaged in “Comfort Women” victim support activities in the United Nations, the European and American Parliaments, and private courts, within the framework of wartime sexual violence and sexual slavery. However, on May 25, 2020, Lee Yong-soo expressed her animosity against referring to the victims as sexual slaves at a press conference. She called it a humiliating expression[5] intended to “make Americans heard and then scared.”

At this moment, the question we have to ask is: if we get rid of the quotation marks from the symbol of the “Comfort Women” obsessively put in quotation marks with the intention of showing reservations, what name should we write down in parentheses? What has Korean society learned for the past 30 years, or 77 years of the “Comfort Women” history if we count from the year 1945?

What does it mean to count the number of living survivors out of the 240 victims registered with the government? Why does Korean society assume that when “Comfort Women” victims pass away, the damage they suffered also disappear just like when the person concerned dies in a criminal case, the lawsuit itself is not validated? Although the “Comfort Women” system is a proven and acknowledged “fact,” why does the “Comfort Women” remain an “issue?” What is being problematized and questioned here?

The government registration of the Japanese military “Comfort Women” survivors and oral recordings of victims’ statements were initiated and sustained through the intervention and activities of not only historians but also women’s studies scholars, sociologists, and anthropologists. However, the recurring anachronistic habit of always entrusting the determination of the final truth to “Rankean historical positivism” is negligent and naive. If truth-finding is not made possible by telling the truth itself but is composed of different interests and positions, shouldn’t more attention be paid to the performativity of testimonies to the past affairs of colonization, war, and authoritarian state violence in a specific context?

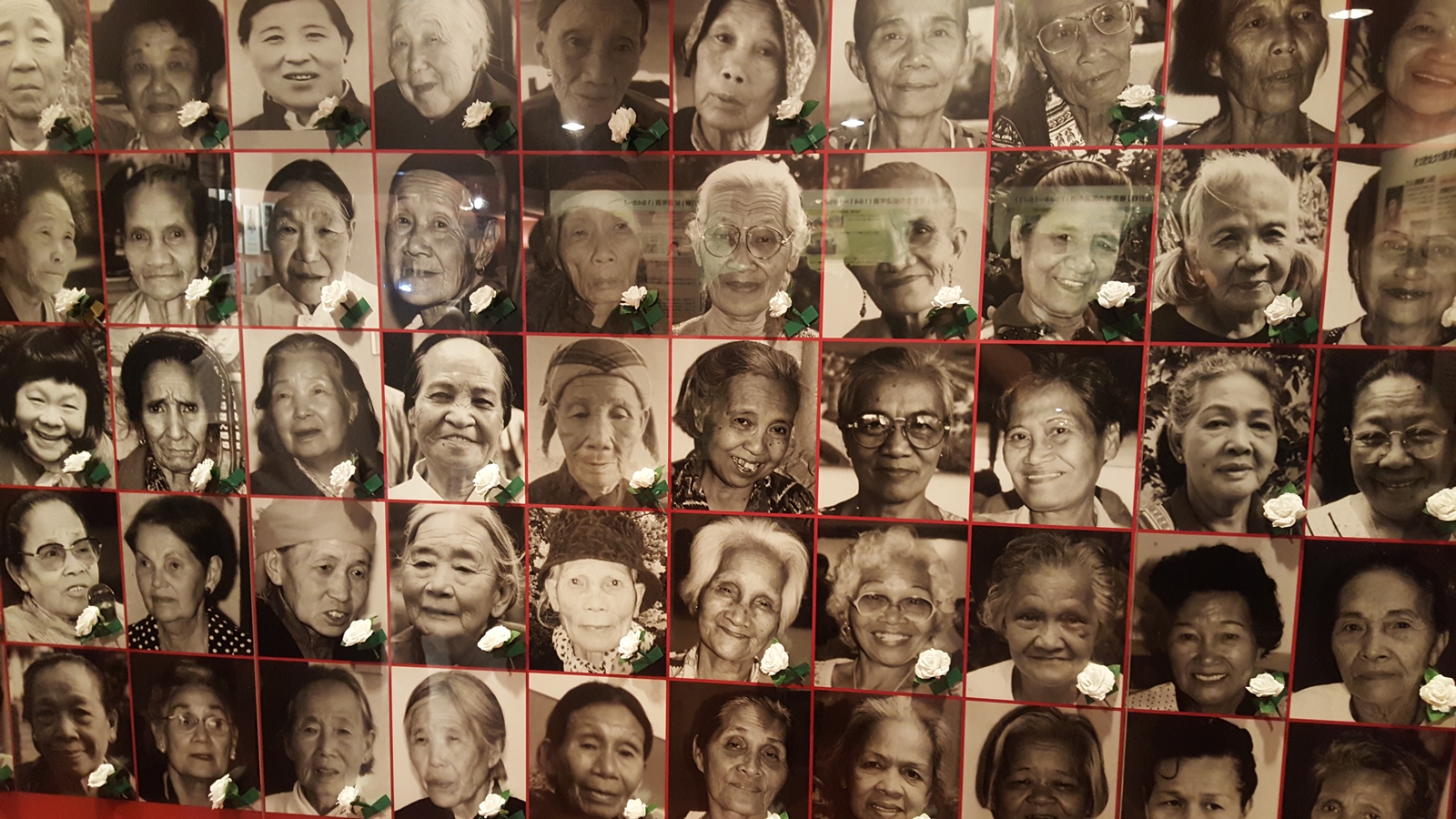

Holocaust survivor Primo Levi emphasizes in his book “The Drowned and the Saved” that the most earnest witnesses to Nazi crimes are his comrades who passed away in extermination camps. There are no perfect witnesses to the times. Nor are “Comfort Women” survivors the ultimate witnesses to wartime sexual mobilization and to “necropolitics.” Even so, they “came out” to disclose who they were and what they had gone through during the war, even on behalf of those who had been killed on the war field. And now they depart this life with the title attached as “Comfort Women.”

In addition, the name “victim,” which anchors survivors in past damage rather than life after testimony, cannot be a qualitative substitute for the signifier “Comfort Women” put in quotation marks. Whether the victims of the Japanese military “Comfort Women” are socially and internationally recognized or whatever name is given to them, there is no way to undo the violence of what they experienced. Mari Oka said, “‘Subaltern’ is a name given to those whose suffering cannot be represented without being subjected to discursive violence,” adding that it’s more important to ask what’s being negotiated when I call someone than to ask her “true” name. “Because we are utterly helpless over past events that have already happened” and “because nothing can expiate the wrongdoing,” we have the responsibility to overcome our present ineffectualness.[6]

Thus, in the era of “One Left” illustrated in a novel written by author Kim Soom, what we have to do now is not count the number of government-registered survivors, but call out the names of “the drowned” between 240 and 200,000 victims and “save” those who are still drowning.[7] In order for that to happen, what do we have to do? At this point, we are reminded of Ichiro Tomiyama’s argument, “If survivors have ‘come out’ through breaking the silence, listeners are responsible for ‘becoming out’ by gaining knowledge through their testimonies.”[8] When victims of structured sexual assault speak out with their faces exposed, there are always other faces in front of them. To those who disclosed who they were, now it’s our turn to reveal who we are.

Footnotes

- ^ Park Jung-ae, “The Entanglement of the Concepts of Teisintai and the ‘Comfort Women’ in Colonial Joseon During the Period of General Mobilization: Later Transition of the Concept of Teisintai,” The Journal of Asian Women, 59(2), 2020, 63.

- ^ James Dawes, “Evil Men” Translated by Byeon Jin gyeong (Paju: Maybooks, 2020), 115.

- ^ Christine Chinkin, “The ‘Comfort Women’ in the Courts of the Republic of Korea: The Last Throw of the Dice?” International Conference on Women’s Rights and Peace 2021 Proceedings, 30-31.

- ^ Segye Ilbo, August 29, 2014. https://www.segye.com/newsView/20140828004633 2022.6.10. Search complete.

- ^ Yonhap News Agency, May 25, 2020. https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20200525115300053 2022.6.10. Search complete.

- ^ Mari Oka, “What is her true name?” Translated by Lee Jae Bong. Edited by Katsuhiro Saiki (Seoul: HYEONAMSA, 2016), 28-29, 254.

- ^ There is no accurate record of the number of the Japanese military “Comfort Women.” However, considering the Japanese army guidance to establish a “comfort station” for every 100 soldiers of 3.5 million Japanese land, sea and, air forces and the replacement of “Comfort Women” during the long war, the number is estimated somewhere between 50,000 and 200,000, and yet, given the testimony of victims that the Japanese military set up a number of unofficial “comfort stations” in occupied territories including Wuhan in China, the Philippines, and Indonesia, these figures become more ambiguous.

- ^ Kwon Kim Hyun-young, “Silence became words, but did words become meaning?” “War, Women, and Violence: Remembering the ‘Comfort Women’ Transnationally,” Critical Global Studies Institute Mnemonic Solidarity e-series, 2019, quoted in 70, and Ichiro Tomiyama, “What Comes ‘After’ the Testimonies: When Violence is No Longer Just Somebody Else’s Pain.”

- Tag

- #survivor

- Writer Hunmi Lee

-

An international political scientist and head of Academic Planning at the Research Institute on Japanese Military Sexual Slavery