“Until we find each other, we are alone.” - Adrienne Rich

Reflecting on the significance of women’s solidarity, the 2023 webzine Kyeol has curated a special feature with the aim of introducing international networks that focus on addressing wartime sexual violence and advocating for women’s human rights. Women in Black, a global network for the women’s peace movement, originated in Jerusalem in 1988 when a group of women dressed in black staged a silent demonstration to protest the 25th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of Palestine. Recognizing the diverse experiences of war, militarism, and violence that women face in different regions and circumstances, Women in Black perceive themselves as a platform for communication and a catalyst for action, resisting being a rigid organization. In this feature, we will delve into the written interviews conducted by the International Law and “Comfort Women” Seminar team at Seoul with Women in Black members based in London and Belgrade.

A Conversation with

Stanislava Staša Zajović of

Women in Black Belgrade Part 2

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

What is the significance of collaborating with artists in the Women in Black Belgrade initiative, and how does this collaboration take place? Additionally, if the combination of activism and art has produced certain results, what are they? I heard that during a campaign initiated on July 7, 2010, to erect a monument titled “One Pair of Shoes, One Life,” 8,732 pairs of shoes, symbolizing the number of genocide victims, were collected from various regions of Serbia. You have also previously mentioned the need to create an aesthetic dimension of resistance to the wars carried out in our name. We are curious about the political impact of this monument and the effects it had on those who encountered it.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

“LedArt,” a group we have collaborated with for 30 years, stated that ethics take precedence over aesthetics when living in a country where war is waged in your name. In partnership with them, we have developed an aesthetic of resistance. As the public monuments we erected were all destroyed by right-wing forces, we are now creating individual monuments. During our recent endeavor, we visited a cemetery and requested the gravedigger to give us a piece of stone inscribed with the number 8372.

Shoes carry profound significance. When I participated in the march in Srebrenica, I had the opportunity to meet numerous survivors, many of whom had escaped without shoes. Our goal was to collect as many shoes as the number of people who had fled without them, but regrettably, we were unable to amass such a large quantity. Let’s assume that people from Leskovac, Krushevac, and other cities donated those shoes. Each time we asked someone for shoes, they were also asked to write a message to the people of Srebrenica. This act itself was highly significant as it symbolized the socialization of pain. As a result, we managed to accumulate hundreds of shoes.

Creating an atmosphere of compassion is an emotionally and morally significant endeavor, yet it is challenging to achieve in Serbia. Due to the lack of empathy, the consequences of the war that Serbia waged are now affecting the Serbs themselves. The crimes committed under our name must be met with justice, but it is the children who suffer the most as the primary victims of these atrocities. The suffering of every individual should be considered equal, devoid of hierarchical distinctions. We took over the entire Knez Mihailova Street with an array of shoes, prompting a massive mobilization of the police force and leaving everyone curious about what was happening. The victims yearned to hear your thoughts on what was done in your name, and it is our obligation, as individuals striving for humanity and dignity, to respond accordingly.

We were unable to collect a substantial number of shoes as going door to door in Serbia, asking for shoes and messages, was a tiring and challenging process. Back in 2008, when we premiered the film “Women of Srebrenica” on the big screen, it was shown four times without any attacks. That’s because the women in the film conveyed a powerful message of peace, evoking profound emotions and moving people to tears. However, we are now facing attacks due to Srebrenica, which is disheartening and troubling.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

We heard that while you were working at the “Center for Antiwar Action,” you noticed that activists involved in the peace movement were overlooking gender inequalities and using patriarchal language, and you recognized the need for a feminist-led peace movement to resist militarism. We assume such concerns might have influenced your decision to initiate the Women in Black movement. We’d like to know how your feminist perspective and engagement with feminists have impacted the process of conducting the Women in Black activities.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

When a problem arises, we can resolve it through open communication and explanation, so I don’t consider it a conflict. From the very beginning, there were men involved in the Women in Black movement, but they had to undergo a specific collective education process. Interestingly, Women in Black Belgrade is the only group that has never encountered issues with male participation. Among them, there were deserters, anti-liberalists, gay men, and more.

Men have been part of our movement since its inception, and we have always collaborated with them. However, I noticed that men primarily focused on addressing public needs, which left me feeling uneasy as it undermined the significance of women expressing their own perspectives and opinions. In response, they reassured everyone, emphasizing the importance of open dialogue among us to avoid misunderstandings. I believe this approach is a powerful way to explain the significance of interacting with others and the importance of women being visible in public spaces. Learning and growing together were of great importance to us. Additionally, we collaborated with transgender individuals, which held significant meaning as an expression of solidarity, not solely for the specific projects we undertake.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

The preparation process for the Women’s Court appears to have been extensive and thorough. You mentioned that “the politics of feminist ethics of care and responsibility has resulted in the production of new feminist knowledge.”[1] Can you share your thoughts on what feminist ethics means to you or to Women in Black Belgrade, as well as the feminist knowledge that has been produced through the Women’s Court? In addition, you mentioned that the activists involved in organizing the Women’s Court experienced trauma, including feelings of guilt, throughout the process. We wonder what kind of responses, struggles, and collective efforts there have been in response to the trauma.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

The process of organizing the Women’s Court spanned five years. It was a unique court because, during that period, we collaborated with women from 100 cities in the former Yugoslavia and brought together women from seven different countries.

The feminist ethic of care entails not only taking care of myself but also extending care to the victims of crimes committed against others.

I firmly believe that providing care and support to those affected by crimes committed in our name represents a new paradigm of knowledge and ethics.

Since the onset of the war, we have consistently opposed it. However, when a crime is committed in your name, it becomes an undeniable reality, and all individuals must be held accountable for their actions. If only a few people discuss crimes, it signifies that the majority is indifferent to the suffering of the victims. This indifference will inevitably lead to severe consequences in the future. Therefore, all nations must step forward to condemn the committed crime.

This process transcends mere decency and compassion; it also has a positive impact on mental health. Individuals who commit killings during the war and evade punishment carry the weight of war within themselves upon returning home. In light of this, it is crucial for women to connect with the mothers of soldiers who have been deployed to war. They should engage in dialogue about the true implications of a soldier returning home alive from war and the struggles they faced to prevent their sons from being sent to battle. The experience of a woman who lost her job due to factory privatization differs from that of a woman who lost three sons to murder. However, through ongoing meetings and conversations, I have come to realize that empathy can develop among individuals.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

You have highlighted the fact that women from the former Yugoslavia region were not all in the same position, underscoring the significance of acknowledging the existing differences and seeking common ground among them. We wonder how women with diverse positions and circumstances reconciled their ideas within the Women’s Court and what specific process they employed to foster mutual understanding of each other’s situations.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

Bringing women from diverse positions together posed a significant challenge. In addition, not all women had the same level of knowledge, particularly those residing in rural areas who lacked the privilege of attending school. Meanwhile, Rada Iveković,[1] a renowned philosopher in Yugoslavia, studied Hannah Arendt and regularly delivered lectures on feminist epistemology. This means that women, regardless of their educational backgrounds, could embrace the philosophies of scholars including Hannah Arendt, Karl Jaspers, and Hans Jonas. It suggests the importance of not underestimating individuals based on their education or background, but rather treating them with respect.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

There was a particular scene in the writing that deeply resonated with us. It depicted the challenging reality faced by women from diverse backgrounds, depending on the regions they inhabited during the war, when they lived together in Belgrade after the war. Among these women, there were those who came from the aggressor nation, others who had to send their sons, husbands, or brothers to the battlefield living in war-affected areas, and even those who were in relationships with men associated with the perpetrator group. Given the circumstances, we are curious about the nature of the relationships that these women forged and how they navigated their shared existence. It appears that they must have actively pursued and practiced a “feminism that rejects and transcends racism” to sustain their relationships. We would like to hear specific stories that shed light on the aspect.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

When Women in Black celebrated its 30th anniversary, women from all over the former Yugoslavia voluntarily gathered in Belgrade, driven by their strong desire to be there. They cherish the sense of protection they feel when they are in our midst. They demonstrate resilience in the face of challenges, drawing upon their extensive activism experience and the support they have received. They enjoy spending summers together, socializing, and living on their own terms free from rigid schedules. They have formed a strong bond of friendship, collaborating, sharing tears and laughter, and cooking together. Their love for coming to Belgrade is evident as they often gather in nearby accommodations to spend time together. In Serbia as a whole, the issue lies not in recognizing rape as a war crime, but rather in the lack of support for women while simultaneously acknowledging war veterans.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

We are keen on comprehending the circumstances confronted by individuals residing in areas where perpetrators or accomplices regain power after the Women’s Court in 2015. Specifically, We are curious about the perspectives of Women in Black Belgrade regarding non-binding courts, considering that they persistently encounter perpetrators who roam freely in their communities. In such cases, how are the feelings of resentment and the desire for revenge, arising from the perpetrators’ impunity, addressed and acknowledged?

Stanislava Staša Zajović

Femicide rates in Serbia have reached alarming levels, surpassing other forms of homicides. In the past year, 24 women lost their lives within a span of 12 months. This year, in just 4 and a half months, the number has already reached 18. This situation has escalated to a brutal extent, affecting all aspects of society. Even programs aired on national television appear to resemble criminal activities. Since the Serbian people have no other media options apart from the mainstream media, there is a pressing need to prohibit and eliminate all such programs. The current situation is even worse than it was in the 90s.

Women in Serbia are experiencing desperation in various aspects of their lives. Unfortunately, the Serbian government and prosecutors are failing to take effective action. Although the police occasionally apprehend perpetrators, a prevailing culture of impunity persists at all levels. This is profoundly disheartening, particularly for children who witness and internalize this violence, potentially perpetuating a cycle of future criminal behavior.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

We would like to learn about the recent activities of Women in Black Belgrade. Furthermore, We are curious if there are any activities related to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War, as well as any concerns or opinions you would like to express.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

Last year, we organized approximately 20 street demonstrations across Serbia to protest against the Ukraine War. We perceive Russia as an imperialist criminal state that has invaded Ukraine and we collaborate with Russian opponents of the war, refugees in Belgrade, deserters, and anti-war activists. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an arrest warrant against President Putin for war crimes. We firmly believe that Serbia should impose sanctions on Putin and denounce any propaganda that supports him. Our commitment lies in standing in solidarity with Ukrainian civilians and Russians who are against the war.

Footnotes

Related contents

-

- A Conversation with Stanislava Staša Zajović of Women in Black Belgrade (1)

-

Women who dare to speak out about sexual violence experience overwhelming anxiety across various aspects of their lives.

- Writer Stanislava Staša Zajović

-

As a co-founder and activist of “Women in Black,” Stanislava Staša Zajović has played a pivotal role in leading a movement to support women who were victims of sexual violence during the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Currently, she continues to be actively involved in organizing networks for women’s rights and peace, as well as campaigning against the ongoing Ukraine War.

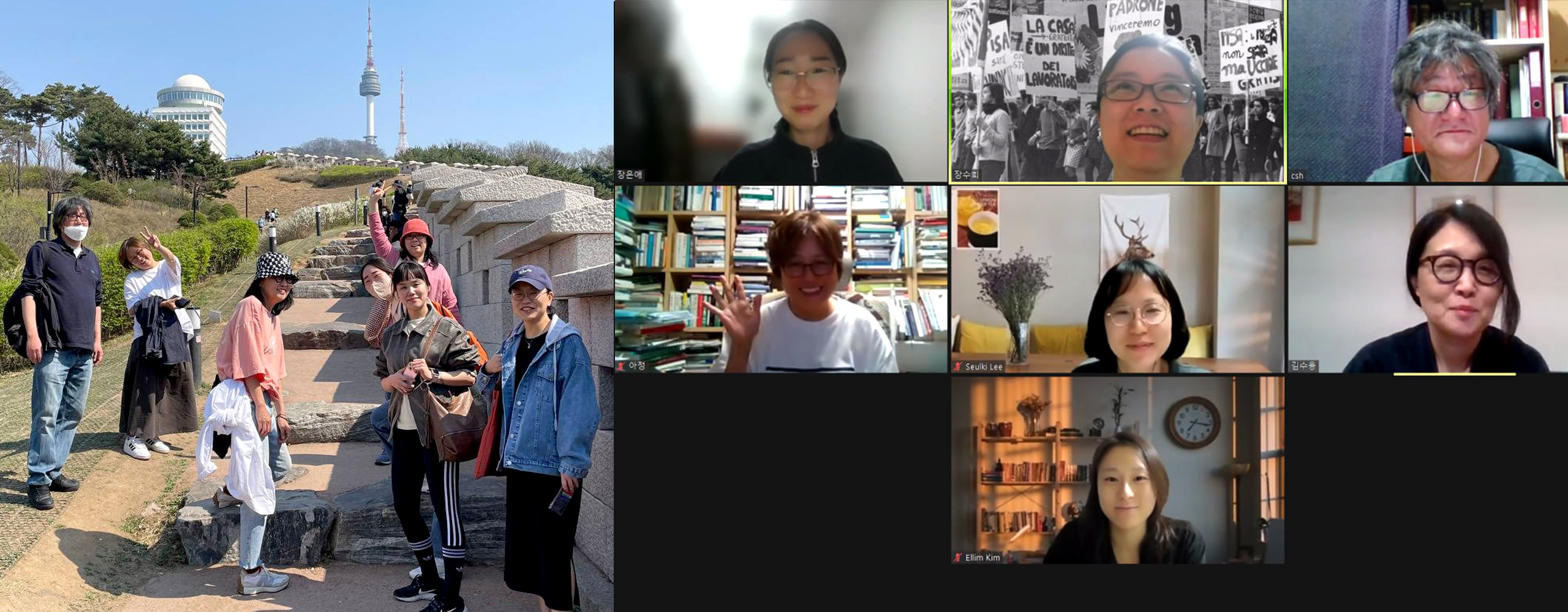

- Writer International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

-

The International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team started its first season in 2020, which was the 20th anniversary of the “Women's International War Crimes Tribunal on the Trial of Japan's Military Sexual Slavery in 2000”. Researchers of various majors have come together every other week to read international law-related materials, and have studied gender-based violence, including the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue, from a new perspective in a contemporary awareness of the issue. Through this seminar, we learned that international law, which is still being developed, is an ongoing endeavor.

During the past three years, there were two rulings related to the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue in Korea. One became a pioneering precedent acknowledging the Japanese government's responsibility for reparation for the Japanese military “Comfort Women” system, which is a crime against humanity by the Japanese Empire. The other recognized the Japanese government’s state immunity and dismissed the lawsuit of the plaintiffs who were the victims of the Japanese military “Comfort Women” system. Our seminar team has read various reports, verdict statements, written opinions, and interrogations on prisoners of war on the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue, and takes great interest in gender-based violence in armed conflict, the issue of impunity for gender-based violence in international war crime trials, as well as colonialism as a criminal act and the impunity for it.

We are delighted to be able to interview Ms. Sue Finch in Women in Black London and Ms. Staša Zajović in Women in Black Belgrade, as we have been reading various sources and thinking about what kind of issues could be raised in tangible history.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team members: Kim Sooyong, Kim Ellim, Sim Ajung, Lee Seulki, Lee Eun-jin, Lee Jieun, Jang Soohee, Jang Wona, Jang Eun-ae, Cho Sihyun, Hong Yoon-shin and Furuhashi Aya.