“Until we find each other, we are alone.” - Adrienne Rich

Reflecting on the significance of women’s solidarity, the 2023 webzine Kyeol has curated a special feature with the aim of introducing international networks that focus on addressing wartime sexual violence and advocating for women’s human rights. Women in Black, a global network for the women’s peace movement, originated in Jerusalem in 1988 when a group of women dressed in black staged a silent demonstration to protest the 25th anniversary of Israel’s occupation of Palestine. Recognizing the diverse experiences of war, militarism, and violence that women face in different regions and circumstances, Women in Black perceive themselves as a platform for communication and a catalyst for action, resisting being a rigid organization. In this feature, we will delve into the written interviews conducted by the International Law and “Comfort Women” Seminar team at Seoul with Women in Black members based in London and Belgrade.

A Conversation with

Stanislava Staša Zajović of

Women in Black Belgrade Part 1

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

Please introduce yourself.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

My name is Staša Zajović, and I am a co-founder and activist of Women in Black, which was established in 1991. I was also involved in the Yugoslav Feminist Network, the precursor to Women in Black. The last meeting of the Yugoslav Feminist Network took place in Ljubljana in June 1991, and the first feminist conference in Eastern Europe was organized in Belgrade in 1978. All of them are part of our feminist heritage.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

What significance do international norms on women’s rights established by various international organizations, including the United Nations, hold for the Women in Black movement? Do the discourse and keywords on women’s rights presented by the United Nations have a meaningful influence on the activities of Women in Black? We are also curious to know if Women in Black Belgrade has participated in shaping international norms for women’s rights.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

As a civil society organization, we strongly believe in the importance of fighting for the rule of law and liberal democracy while engaging in activities independently from international organizations. Since 1993, organizing alternative conferences has been a vital undertaking for the United Nations. For instance, in June 1993, approximately 20 of us participated in the World Conference on Human Rights held by the United Nations in Vienna. During this conference, we had our first encounter with Bosnian women who shared their testimonies of experiencing war rape. This meeting marked a historic moment when the United Nations acknowledged that women’s rights are human rights.

In 1994, I also attended the World Population Conference held in Cairo. I was involved in a women’s network that opposes fundamentalism, which entails the exploitation of religion, cultural heritage, and race for cultural purposes, together with women from Africa, Arab countries, and other nations. The conference was noteworthy as civil society organizations were more numerous in representation than the United Nations itself. Furthermore, it led to the official recognition of abortion as a fundamental women’s human right. During this time, I became aware of a far-reaching, global, and menacing movement that opposed gender ideology.

I have witnessed fundamentalists from various backgrounds collaborating. Christian and Islamic fundamentalists have initiated an organized war against women, and this disturbing trend has taken an official form in present-day Serbia. These assaults began in the Vatican and subsequently spread to countries such as Poland, Croatia, and beyond. In Serbia, attacking women based on their low fertility rate is becoming a component of a dangerous nationalist policy.

I was also invited to the Fourth World Conference on Women, which took place in Beijing in 1995. Unfortunately, I couldn’t attend as it coincided with the expulsion of people from Krajina (editor’s note: an internationally unrecognized Serbian state that declared independence from Croatia).

A significant day to remember is May 25, 1993, when the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in The Hague. This tribunal was tasked with prosecuting individuals accountable for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed in the former Yugoslavia. Without The Hague War Crimes Tribunal, we would have remained unaware of the identities of those who were convicted for their crimes in the former Yugoslavia. Hence, we must remember the actions taken by the United Nations.

Thanks to a UN delegation that attentively listened to feminists, activists, victims of sexual violence, and legal experts, a remarkable milestone was achieved at the United Nations. For the first time in history, rape was acknowledged as a war crime. This significant development occurred during the Yugoslav wars, primarily due to the collaborative efforts of Bosnian women and Bosnian women activists. Although they were not UN officials, their unwavering commitment to women’s liberation led them to make a substantial contribution.

The 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) holds immense significance as it expanded the scope of crimes against humanity by including the concept of sexual violence. However, the Rome Statute remains unratified by Russia, the United States, China, and Ukraine. While these countries recognize the authority of the ICC, with 123 countries having signed on to the Rome Statute, they refuse to abide by the statute when it comes to indicting President Putin as a Ukrainian war criminal. As such, the implementation of international human rights norms is related to geopolitical dynamics and the offensive against the United Nations.

A groundbreaking development took place with the establishment of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security. We consider this resolution a crucial mechanism to exert pressure on states, primarily due to Article 11. This article explicitly assigns the responsibility to the state for prosecuting and eliminating impunity for crimes such as genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes, including sexual violence against women and girls.

Currently, our collaboration with the United Nations has significantly diminished. This decline in engagement is attributed to the reduced influence of the United Nations in comparison to major powers. For instance, an agreement was initially reached between Ukraine and Russia, mediated by the United Nations and Turkey, which allowed for the export of grain through Ukrainian ports. However, Putin’s response to European and Western sanctions by blocking off the Black Sea resulted in dire consequences for numerous African countries that depended on Russian and Ukrainian grain.[1] UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has expressed concern about a widespread global campaign aimed at undermining the UN.

During the clashes in Donbas in 2014, we held protests in front of the Russian Embassy. Ukrainian and Russian women expressed their opinions at the forum, calling for the deployment of UN peacekeepers to Donbas. However, it is evident that peacekeeping forces, like the Russian peacekeeping forces sent by Putin with political intentions, often assume highly contradictory roles.

Another example is found in Bosnia, where UN peacekeepers themselves committed sex crimes. The Women in Black campaigned for the abolition of UN peacekeepers’ immunity, which was repealed in 2016. However, the repeal does not guarantee the prevention of future incidents of sexual assault by UN peacekeepers in other regions, such as Syria, Yemen, or Ukraine. I believe it is crucial to deploy civilian peace corps in Ukraine alongside peacekeepers sent by international organizations.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

We are interested in hearing your perspective on the issue of silence surrounding wartime sexual violence. In Korea, many victims of Japanese Military “Comfort Women” remained silent until Kim Hak-sun bravely testified about her experience as a “Comfort Woman” in 1991. Unfortunately, such silence continues to persist today, leaving victims of wartime sexual violence worldwide voiceless. We would like to know the viewpoint of “Women in Black” Belgrade regarding the resistance or radicalization of silent protests when victims choose to remain silent or are compelled to be silent.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

The rape of women was regarded as a wartime obligation, while the harm inflicted upon women during conflicts was not adequately recognized. Consequently, women have been forced into silence. Having collaborated with women who have experienced rape, I can attest that numerous women continue to suffer in silence. It is not solely a matter of rights; it is intertwined with the burden of societal stigma and the fear of retaliation against their families, compelling them to remain silent to ensure their family’s safety.

Women who dare to speak out about sexual violence experience overwhelming anxiety across various aspects of their lives.

Many women we are acquainted with have never disclosed the trauma they endured to their husbands or siblings. They have remained silent, not only within their social community but also on a national level. The concept of protecting women is often viewed as a matter of male honor, which further perpetuates their silence.

For instance, during the Kosovo War, approximately 200,000 individuals were mobilized in Serbia. While collaborating with women from central Serbia, which is situated approximately 50 kilometers away from Kosovo, I asked them if they had ever inquired about men’s experiences in Kosovo and whether they believed any sexual violence had occurred. The responses were negative. Considering the alarming statistic that 30 percent of Serb women have become victims of domestic violence resulting in death, how can we assert that they are safe?

In Serbia, Serb women from Kosovo are discouraged from discussing the sexual violence perpetrated by Albanians. However, during my conversations with Albanian women from Kosovo, they openly shared their experiences of rape committed by Serbians. This suggests that the stigma surrounding victims of sexual violence is more pronounced in Serbia than in Kosovo. Even for Bosnian and Croatian women, speaking out about the rape they endured at the hands of Serbs has never been an issue.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

The Japanese Military “Comfort Women” movement in Korea extends its support and solidarity to women who are victims of wartime sexual violence in other conflict zones, such as Congo and East Timor. The atrocities of killing and rape during wartime give rise to numerous social issues that persist even after the war ends. For example, issues such as childbirth resulting from sexual violence, the subsequent generation born as a result of such violence, and HIV infections are cases where wartime killings and rape have extended into post-war societal problems. How does Women in Black Belgrade intervene in addressing the aftermath of war-induced damage, in addition to the involvement in the anti-war movement? What specific forms of direct action do you employ? Regarding these questions, we would also like to know about the strategies and methods employed by Women in Black Belgrade, as a liberal organization, in providing medical and psychological support to victims of wartime sexual violence.

Stanislava Staša Zajović

Since the start of protests in 1991, we have faithfully gathered at Republic Square every Wednesday to demonstrate against war and mobilize efforts to combat wartime sexual violence. We persistently advocate for justice for the victims of sexual crimes and exert pressure on Serbia to recognize wartime rape as a war crime. A significant milestone was reached in 2015 when the United Nations designated June 19 as the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict. Each year on this day, we organize an annual event at Republic Square to take a stand against sexual violence targeting women.

Additionally, immediately after the conclusion of the Yugoslav Wars, we initiated a series of meetings with our former Yugoslav acquaintances in a third country. This strategic approach proved vital in establishing connections and fostering channels of communication. We have also organized multiple visits to the crime scenes, where we met with the families of the victims, expressed condolences, attended funerals, and closely monitored the trials of war criminals at the Special Court since 2005. Through our sustained contact with them since 2005, the families of the murder victims, primarily from Bosnia and Croatia, have actively participated in these events.

In 2015, women from diverse nationalities and geographic regions established the Women’s International Court for the Former Yugoslavia and Successor Countries (hereinafter Women’s Court). Within this organization, witnesses formed a network known as the “Mothers in Solidarity for Peace.” These women are mothers of sons who were killed either in Srebrenica or during the NATO bombing of Radio-televizija Srbije (RTS) in 1999.[1]

The women who provided testimony at the Women’s Court have formed their own informal networks. On the island of Brač, there is a house that Croatian women took over from Germans, where women of all nationalities gather for a two-week vacation every year. We come together and engage in conversations twice a year at this location. During this process, we have witnessed remarkable growth among women who, despite lacking formal education, display a profound enthusiasm for learning about feminist practices and other related concepts collectively.

We do not engage in reconciliation programs as we don’t believe in empty apologies without proper judicial proceedings. Instead, our focus is on fostering mutual trust. This is because the international community has been largely responsible for the decline of reconciliation efforts, reducing the concept and practice of reconciliation to mere protocol and rendering them meaningless and hollow experiences for government officials.

Footnotes

Related contents

-

- A Conversation with Stanislava Staša Zajović of Women in Black Belgrade (2)

-

The feminist ethic of care entails not only taking care of myself but also extending care to the victims of crimes committed against others.

- Writer Stanislava Staša Zajović

-

As a co-founder and activist of “Women in Black,” Stanislava Staša Zajović has played a pivotal role in leading a movement to support women who were victims of sexual violence during the civil war in the former Yugoslavia. Currently, she continues to be actively involved in organizing networks for women’s rights and peace, as well as campaigning against the ongoing Ukraine War.

- Writer International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team

-

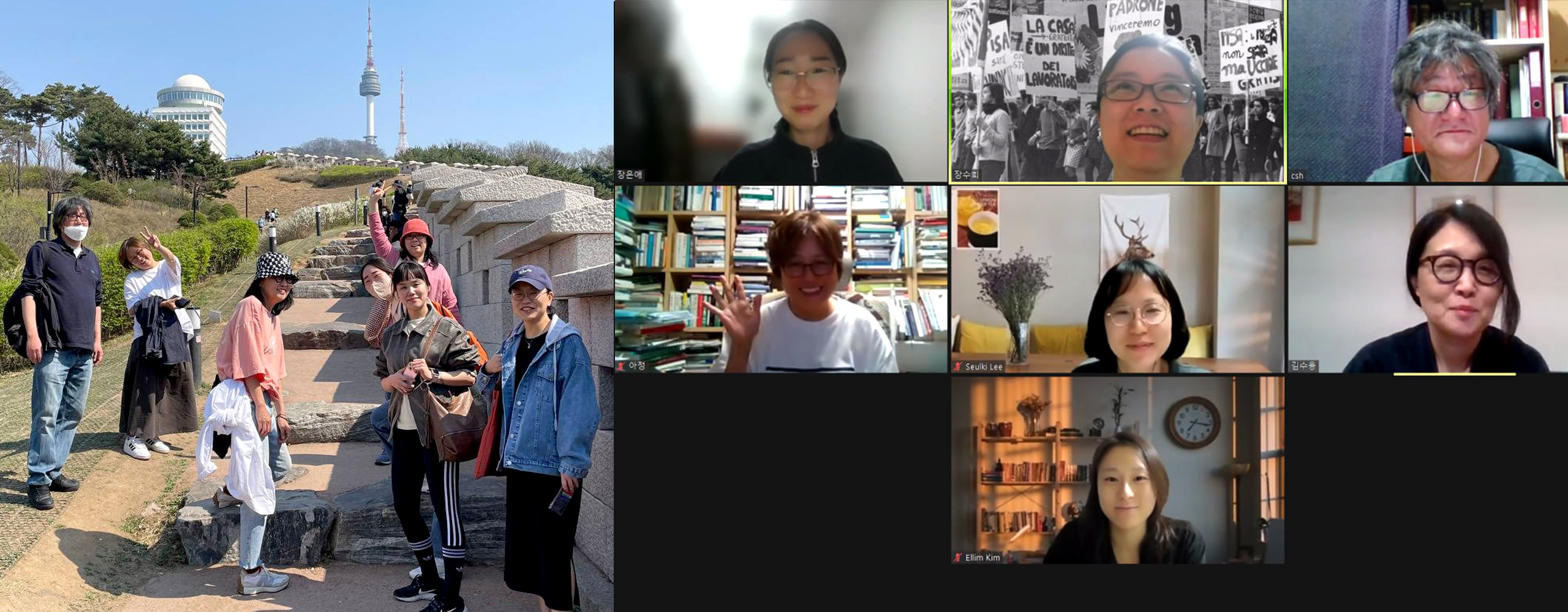

The International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team started its first season in 2020, which was the 20th anniversary of the “Women's International War Crimes Tribunal on the Trial of Japan's Military Sexual Slavery in 2000”. Researchers of various majors have come together every other week to read international law-related materials, and have studied gender-based violence, including the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue, from a new perspective in a contemporary awareness of the issue. Through this seminar, we learned that international law, which is still being developed, is an ongoing endeavor.

During the past three years, there were two rulings related to the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue in Korea. One became a pioneering precedent acknowledging the Japanese government's responsibility for reparation for the Japanese military “Comfort Women” system, which is a crime against humanity by the Japanese Empire. The other recognized the Japanese government’s state immunity and dismissed the lawsuit of the plaintiffs who were the victims of the Japanese military “Comfort Women” system. Our seminar team has read various reports, verdict statements, written opinions, and interrogations on prisoners of war on the Japanese military “Comfort Women” issue, and takes great interest in gender-based violence in armed conflict, the issue of impunity for gender-based violence in international war crime trials, as well as colonialism as a criminal act and the impunity for it.

We are delighted to be able to interview Ms. Sue Finch in Women in Black London and Ms. Staša Zajović in Women in Black Belgrade, as we have been reading various sources and thinking about what kind of issues could be raised in tangible history.

International Law & “Comfort Women” Seminar Team members: Kim Sooyong, Kim Ellim, Sim Ajung, Lee Seulki, Lee Eun-jin, Lee Jieun, Jang Soohee, Jang Wona, Jang Eun-ae, Cho Sihyun, Hong Yoon-shin and Furuhashi Aya.